The Marxist Theory of History

The Marxist Theory of History

The existence of humans as humans is the result of millions of years of interaction with organic nature itself and, as a prerequisite, with inorganic nature. However, once humans emerged, they began to transform nature to their advantage for the continuation of their species. Altering nature for vital interests provided them with their first knowledge about it. Therefore, the intelligent, speaking, knowledgeable, active human Adam of the sacred books is not a beginning but a product of natural history, a result…

Humans develop their knowledge through their interactions with nature during production in all aspects of themselves. Ultimately, beyond practical interests and the object of biological needs necessary for survival, they consider nature as a mental object of thought (which is undoubtedly a result of the former and its negation). The systematic reorganization of past knowledge leads humans to the level of organized knowledge—to science.

The fact that humans examine endless subject matter—in other words, that matter carries within itself unknowns awaiting human discovery in both its infinitely indivisible smallness and infinitely vast greatness—brings about the infinite development of science and knowledge that delves deeper into it and actually necessitates it. Thus, the effort to reach an end in knowledge or absolute knowledge is nothing but a metaphysical illusion.

Every science or scientific endeavour takes place within the limitations of its historical-social relations. In this framework, scientists can only study and examine nature at the level permitted by their own era. Newtonian physics and modern physics are typical examples in this regard. Undoubtedly, the developmental process of every area of human thought bears witness to this fact…

As a science, Marxism is a product of the 19th century’s scientific development—the era in which Marx and Engels developed their science. In “Dialectics of Nature,” Engels says that contemporary science gave birth to dialectics. Engels also compares the position of dialectics against metaphysics to that of the railroad against medieval ox carts. He states that every new development in science will lead to a new deepening in dialectics and in Marxism in general, and moreover, that theory should be developed parallel to science…

The reader should consider this: the superiority of the railroad over ox carts is obvious. But what is the superiority of aeroplanes that exceed the speed of sound and spacecraft opening toward the depths of space over the railroad?

It is a well-known fact that the 20th century saw the multidimensional development of science. It is a necessity for Marxism to be developed with new scientific data. This necessity becomes more apparent in today’s world, where science is shaped according to bourgeois interests and ideology, and development is permitted only through these channels. However, all bourgeois distortions enter Marxism through this very door. Therefore, what is put forward in the name of Marxism within this framework must be subjected to scientific filtering. Undoubtedly, the criterion for this filtering will be which social class’s interests are being served by what is presented. The criterion of reality for any theoretical scientific discussion is, of course, practice.

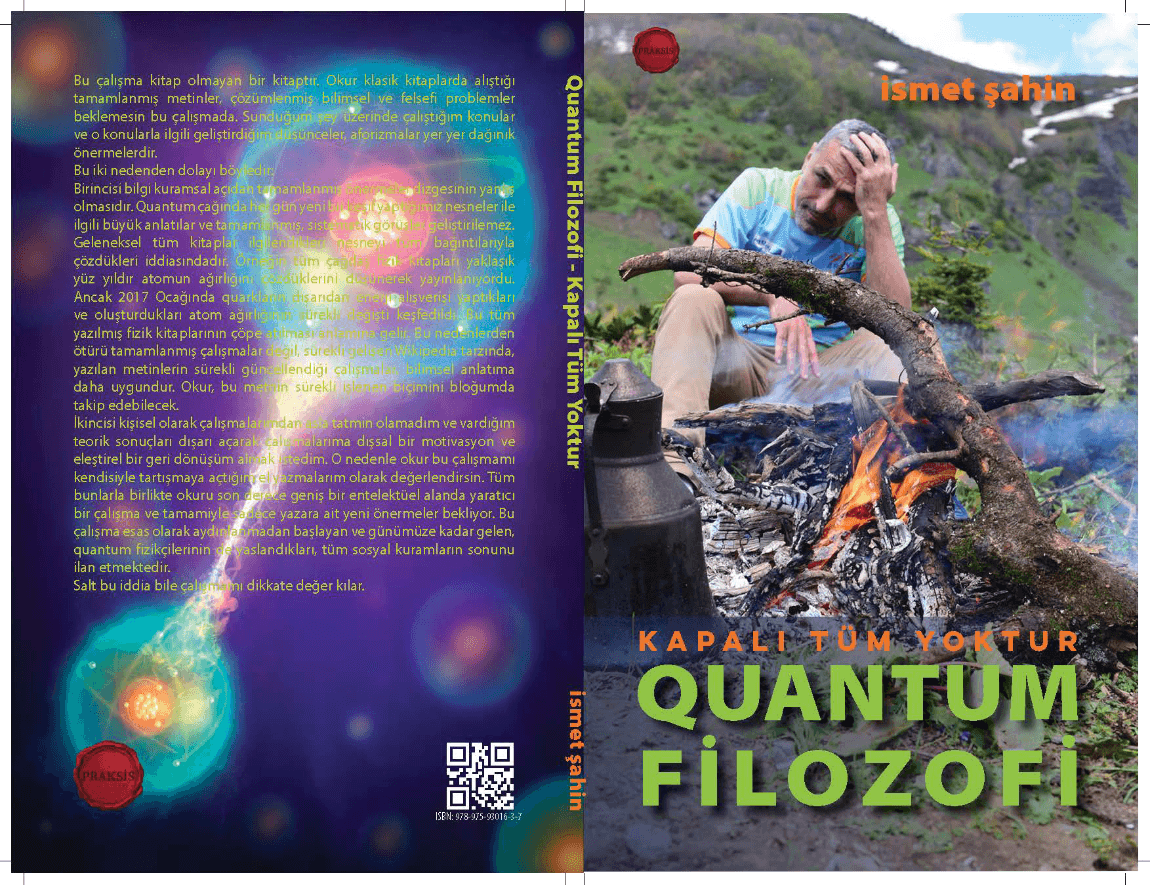

In this framework, the theoretical view we will subject to criticism below is Dr Hikmet Kıvılcımlı’s book titled “The Theory of History,” which has been republished. Dr. Kıvılcımlı believes that Marx and Engels were deficient in revealing the moments of historical development due to the insufficiency of scientific development in their era, and that he himself will complete this deficiency. Now, let’s see to what extent Dr. Kıvılcımlı has realized this idea.

HISTORY AS A WHOLE

Dr. Kıvılcımlı deduces his “Theory of History” from analyses of ancient history. He explains his reason for extending back to ancient history as “to understand today’s Turkey” (p. 30). To understand today’s Turkey, it was necessary to delve into Ottoman history, from which it emerged (or rather, from which it could never quite emerge). As for the substance of Ottoman history, it became clear that it was a “Renaissance” within Islamic civilization. All the ancient civilizations listed from pre-Sumerian times up to Islamic civilization—while they emerged from each other, being both the same and different from one another—they all showed the same trajectory and conformed to a single law.

He grounds his reasoning by stating that unless it is clearly understood how all the problems extending to the present day stem from a chain of cause and effect reaching back to pre-Sumerian times, no concrete historical event can be properly illuminated. In summary: “Unless the history of a country (yesterday’s events) is properly known, the reality of that country (today’s events) cannot be well understood.”

Undoubtedly, Dr. Kıvılcımlı’s reduction of history to a mechanical sequential series is wrong. This simplistic understanding links the understanding of today to yesterday, the understanding of yesterday to the previous day, and so on. It is the same path followed by worshippers of God to prove God’s existence. Starting from the question of who created you and going back through a series of claims and events to the idea that everything was created by God—and for some reason never reaching the question of who created God—they set their sequence according to their whim and obtain the result they desire.

Within these logical patterns, Dr. Kıvılcımlı summarizes many events up to the formation of the world. To the extent that he reduces history to yesterday’s events and reality to today’s events, Dr. Kıvılcımlı falls into positivism.

Yet, world history did not always exist; the becoming of history into world history is a result. The attainment of a common history by the world, and the conception of history as history as its thought, is a product of capitalism.

The history of a country is encompassed within its reality as an abstract aspect. The understanding of today is not dependent on the understanding of yesterday, nor is the understanding of yesterday dependent on the previous day. On the contrary, the understanding of all past history depends on the understanding of today—of capitalism. Capitalism itself is understood in its totality.

Similarly, Turkish capitalism can be understood as a part of world capitalism within the process of its integration into global capitalism.

The “past” is that which has ended in reality. The “present” carries the past within itself as an abstract aspect. It is clear that the analysis of the “present” will reveal both the past and the ways it connects with the “now.” Just as thought develops from the simple to the complex, from one-sidedness to multifacetedness, so does history.

We can take the simple—something from past history—and examine it on its own. That is, we can study any society at any time and place in history. But if this examination is done without knowing the next stage of development of the society we are studying, we cannot determine the direction of that society’s evolution, and we cannot obtain a result from our examination at that time.

Every historical examination can be done by considering the next moment of development and even the sequence up to today as an a priori reference point in thought: It is clear that the ancestor of humans cannot be known without knowing their anatomy. Understanding which animal herds in various periods evolved towards humans and which were eliminated in nature depends, as a result, on the development of the advanced form—humans—and knowledge about them.

Humans gained binocular vision by the forward shift of their eyes in the skull, allowing perception to be a joint function of both eyes. In the skeletal structures where we find traces of such evolution, we place them at some point in our evolutionary process. Otherwise, the fossils or skeletal structures found carry no meaning beyond piles of bones, because we cannot place them within a historical context or, more accurately, within a sequence.

It thus becomes clear that Dr. Kıvılcımlı’s extension back to Ancient History to understand Turkey is wrong. Can someone who makes a mistake in the general approach to history exhibit a correct approach in examining a part of it? Undoubtedly, yes. Because the particular or singular can only be understood in its relationship with the general.

To understand the truth value of this logical principle, we need to see, along with Dr. Kıvılcımlı, the revolution—or rather, the dialectic of development—of the Ancient Age.

MARX-ENGELS AND THE THEORY OF HISTORY

Dr. Kıvılcımlı claims that despite Marx and Engels’ brilliant notes on Ancient History, they could not develop the theses he is now developing due to the insufficiency of historical and human sciences in their own eras.

Their deficiencies are explained as “the knowledge of prehistory and Near Eastern history was not available in their time” (p. 18).

With the same mechanical causality, Dr. Kıvılcımlı connects the concept of ancient history to prehistory and argues that the concepts of Marx and Engels, who lacked knowledge of prehistory, need to be corrected and developed. We have shown above that this is wrong. Likewise, he recounts the process from the Solar System to the birth of civilizations over dozens of pages without deriving any theoretical result.

If it can be considered a theoretical result at all, he places the solar system within nature and human society within life in parallel with the birth of civilization, establishing a relationship of similarity. However, the laws that play a role in the formation of the world and those that play a role in the birth of civilizations are different—completely so.

The first is dependent on the laws of transformation of many material forms such as mass, energy, velocity, radioactive radiation, etc., while the other is dependent on the laws involved in human interactions with nature and themselves. Undoubtedly, both have a dialectical process, but the first is the dialectic of nature, while the other is the dialectic of humans and society, which are primarily products of the evolution of organic nature.

The lack of knowledge of prehistory does not create a deficiency in the concept of materialist history because the theory reveals the objective laws of historical development. On the other hand, Darwin demonstrated the biological evolution from ape to human, while Marx demonstrated the social evolution, which today has been more fully established. Based on these data, Engels showed the role of labour in the process of becoming human, completing the theoretical framework of the period. Although Dr Kıvılcımlı himself gives different names and does not like these studies, these scientific works continue to be the fundamental works and theories of their respective scientific fields.

NEAR EASTERN HISTORY AND THE MATERIALIST THEORY OF HISTORY

Marx’s theoretical propositions, which have not been surpassed to this day and form the basis of all research on the subject, were formulated with this “deficient” knowledge of Near Eastern history that Dr. Kıvılcımlı mentions.

- Near Eastern history includes Mesopotamia, Sumer, Babylon, Akkad, Assyria, and Egypt, where the main excavations and findings were revealed in the 20th century. Studies have shown that these civilizations are the first civilizations in history; that is, they are the initial points in humanity’s transition from barbarism to civilization.

What is the real value of knowing Near Eastern history in terms of theory? A big nothing, except for a reconfirmation of the theory.

- New findings have two effects on theory: positive or negative. A negative effect occurs when new findings completely falsify the theory. In this case, the theory is shattered, and a new theory arises based on concrete data. Near Eastern studies did not yield such a result. A positive effect occurs when concrete data that are clearly related to the theory emerge, even though data were not previously obtained during the formation of the theory.

A third situation is that the theory may be stuck at an incomplete level of abstraction, i.e., at a metaphysical level within a certain framework. In this case, the concrete finding becomes the logical datum for realizing the abstraction so that the theory can represent real concreteness in thought, or more accurately, reflect reality in its entirety. Although Dr. Kıvılcımlı partially advocates this, historical materialism does not bear this deficiency.

Moreover, the theory is present in its most general form and, on the contrary, requires the examination of various singular historical events—for example, the examination of Turkish history in a historical materialist manner.

Near Eastern history, as concrete historical data, has reconfirmed the materialist theory of history. For a framework that we cannot expand further here, the reader can refer to Serol Teber’s “The Humanization of Nature” and the book “Ancient History” by authors V. Diakov and S. Kovalev.

It can be shown that these concrete data do not contribute to the theoretical structure beyond confirming it; considering that neither Dr. Kıvılcımlı nor others who possess knowledge of Near Eastern history have advanced Marx’s theory one step further or completely negated it. Undoubtedly, this is a subjective approach but it is correct. The reader can see this by looking at the last section of Dr. Kıvılcımlı’s book where he discusses Marx’s theses.

Marx inferred his thoughts—where he defined three types of society and property (Asiatic, Ancient, and Germanic)—from studies of Chinese, Indian, and Turkish societies, Slavic and Romanian clans, the civilizations of Mexico and Peru, and the ancient Celts (Grundrisse, p. 521).

It is clear that historical data provide Marx with sufficient material for the necessary theoretical formulations. The rest is historical detail; the examination of a singular social form occurring or forming at time X in geography Y is undoubtedly a necessity for the expert in that field, but only for them.

We have seen that Dr. Kıvılcımlı’s justification for developing his own theory of history is the “deficiency, weakness” of Marxism on this subject. Now, let’s look at the “Theory of History” he developed based on this justification—or at least thought he developed.

Kıvılcımlı’s THEORY OF HISTORY

Kıvılcımlı derives his “Theory of History” from the examination of ancient civilizations. According to him, civilizations have been considered individually, but their processes of transition to one another have not been analyzed due to the insufficient accumulation of knowledge in that period (Marx-Engels). Yet it is these “transition” periods that give them their characteristics—the laws that enable the transition from one civilization to another. Here is Dr. Kıvılcımlı’s Theory of History:

“In Ancient History, the quantitative leap that enables the transition from one civilization to another could not occur unless fresh human productive forces called ‘barbarians’ intervened. The overthrow and elimination of a decayed civilization have always occurred through the influx of barbarians. For those collapses, we simply find the term ‘Historical Revolution’ appropriate because the collapse of a civilization is also a Revolution. But a social Revolution is the removal of one social class by another within the same society.

A historical Revolution is made by people from another society, more backwards, coming from outside the society. Because it is not a mere Social Revolution, it is replaced by a Historical Revolution.” (Theory of History, p. 24)

To understand this passage where many things are mixed together, let’s proceed with a simple analysis:

- The dynamics of the transition from one civilization to another are the barbarians.

- Barbarians are “human productive forces.”

- As this productive force, the barbarians lead to a Historical Revolution because they cause the overthrow of the “decayed” from the outside, not the overthrow of one class by another as in a social revolution.

- This revolution is carried out not by a more advanced society as we have known until now but by people from another society that is “more backward” and moreover coming from “outside.”

For now, we are just trying to understand the Doctor. Let’s continue. On the same page, he writes:

“The interactions of Historical Revolution that seem to occur between civilization and barbarism on the surface of history are actually the mutual interactions between private property and public property governed by the deepest productive forces; since this contradictory course has continued relentlessly throughout Ancient History, it carries the force of social law. This can be called the Law of Historical Revolution.”

Firstly, in this paragraph, we understand that the “action-reactions” between civilization and barbarism mentioned in the previous paragraph are actually the interactions between private property and public property governed by the deepest productive forces.

Secondly, since this contradictory course stamps all of Ancient History, it carries the “force of a social law.” Thirdly, we now learn that since it carries the “force of a social law,” this can be called the Law of Historical Revolution.

And the last paragraph:

“In this respect, the relations between civilizations and barbarians in ancient history are like electron relations that explain chemical affinities between atoms. Barbarian movements are the nuclear power of the course of history; they operate with the instinct of living beings in the struggle for survival. We will call the dooms that erupt between barbarians and civilizations ‘Historical Revolutions.'” (p. 543, end of the book)

The last paragraph has a uniqueness that does not directly reflect to the reader. That is, Dr. Kıvılcımlı wrote this paragraph after reading Marx’s “Grundrisse.”

We will address the “chemical affinities” between atoms later. Our main sentence is the one that follows immediately: “Barbarian invasions are the nuclear power of the course of history.”

Since Dr Kıvılcımlı believes that his Theory of History explains the law of the course of history, it is better to start by analyzing this.

THE COURSE OF HISTORY

It would be correct to say “the progress or development of the course of history.” It is possible to approach it in two ways. The first is to understand history as temporal passage. In this logical framework, the space through which time passes is always the same world. What passes is time. In this logical framework, revolutions cannot be spoken of in history because revolution is a qualitative change, whereas time progresses quantitatively. This approach also envisages history always within the same social form. Undoubtedly, this form is capitalism. Here, one can easily pass to the eternity of capitalism. Undoubtedly, Dr. Kıvılcımlı does not advance this logical framework to these conclusions, but he too stands on this ground.

This is an abstract metaphysical comprehension of history. He calls the “dooms” that break out during the attacks of barbarians on civilizations “Historical Revolutions.” However, this is nothing but a mechanical displacement. A more predatory animal turning to other hunting grounds to prey on weaker animals is something that always happens in nature. Undoubtedly, for the hunted animal, this is also a doom. But this does not lead to any historical development in the animal kingdom. Otherwise, animals would also have a history, which is not possible.

Contrary to what is often wrongly said, the lack of history in animals is not due to their lack of consciousness of their experiences or their lack of written records. Consciousness does not create history because it is itself a historical product. And it forms and shapes on the material basis parallel to the development of history.

Similarly, a human community that has migrated from place to place for thousands of years has no history. In this mechanical form, it cannot go beyond sequences like “it emerged from here at this time, settled there at that time, struggled with these between such times” for a society or people. Therefore, even if it travels all over the world and struggles with every people it encounters and lives this way for hundreds of years—which is impossible—as long as it maintains the same social form, this people has no history. It is either doomed to die, or it will be absorbed within the history-producing peoples, and this is another kind of death. It is clear that placing “barbarian movements” at the center of the “course of history” is absurd.

**Dr. Kıvılcımlı should have sought the “course of history” not in barbarian movements but in the concrete natural-historical ground that produces them as well. Because classes could not leave their mark on the course of history—since there was no social revolution—Dr. Kıvılcımlı brings in barbarians as the saviors of historical development, as its motor. He mistakenly calls the contribution made by the barbarians to the development of history a “Historical Revolution.”

Clearly, by giving a historical role to barbarians instead of classes in the development of history, he adds a “historical revolution” to the moment of historical development. He defines this “historical revolution” as the “dooms” that erupt between barbarians and civilizations, between rural and urban areas, and ultimately between the primitive commune or public property and private property.

To understand how Dr. Kıvılcımlı falls into these metaphysical conclusions, we need first to examine the Dialectic of Revolution itself and then place it back into its historical and social context.

THE DIALECTIC OF REVOLUTION

Dr. Kıvılcımlı’s “Theory of History” is the ground where he breaks his ties with dialectics. He says, “After every prolonged gradual evolution, civilization suddenly collapsed through the (completely different from social revolution) revolution of barbarian invasions. We call this a historical revolution. Thus, the greatest dialectical law of existence has operated in nature and society.” (p. 58)

Another passage where he mentions dialectics: “The striking force coming to the city from outside was the commune. The changes brought by the commune were revolutionary and sudden… All these internal-external upheavals operated like rhythmic moments of a complete dialectic throughout human ancient history.”

Dr. Kıvılcımlı attributes revolution to random, external forces. Essentially, there are two elements in a revolution. First, the conflicting, opposing two sides or parties within a contradictory whole. Second, the conflict must have developed to a quantitative degree that can lead to a qualitative leap. Otherwise, no matter how many “dooms” occur, a revolution is impossible.

Revolution is the necessary, causal, and objective internal development that leads to a qualitative change at a certain stage.

Everything exists with its opposite, and this opposition gives rise to conflict. Conflict is the source of motion and development. Development and revolution occur when quantities accumulate or increase to a point that leads to a qualitative leap. This is revolution. The old structure has undergone a qualitative change. The revolution continues until another qualitative change (revolution) occurs.

The revolution that ensures the development of existence is inherent in the nature of existence. That is, existence exists with its motion. The important point is that the development of existence towards revolution is the spontaneous result of internal contradictions and conflicts. This is the general dialectical law of qualitative-revolutionary changes occurring in nature, society, and thought.

Now we need to answer this question: Can the collapse of civilizations by barbarian invasions be called a revolution? To say so, the barbarians must be one of the two opposing poles within a whole. If not taken in this way, what we are talking about is not revolution but wars leading to defeats, destructions, burnings, and often the plundering of countries. It is naive to confuse such wars with dialectical conflict.

Dr Kıvılcımlı finds two contradictory elements to create his historical revolution: these are barbarism and civilizations that could not make their social revolutions. He says, “The greatest law of the course of ancient history lies in the contradiction between barbarism and civilization.” (p. 23) To clarify the subject and show the Doctor’s error, we need to place the revolution we previously discussed in abstract terms back into its social-historical context.

Earlier, we stated that every social form is shaped and conditioned by a mode of production. A social form is essentially production relations. Initially, human communities and later, as they became more structured, society itself is the product of the relationships people necessarily enter into with nature and each other during the production of their material lives—or more precisely, these relationships themselves.

Society and humanization are natural results of production, and humans undertake to transform nature for their own benefit through labour (work) for food, shelter, clothing, etc. “Animal herds are content with what they find; human communities produce with their labour.” —Engels.

Production emerges as the first historical action of humans. But this production is also the production of human historical development.

Marx says, “The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political, and intellectual life.” A change in the mode of production will lead to a rapid or slow change in the social, political, and intellectual life process. This shows us that we need to look for the key to social-historical development not in barbarian invasions but in the mode of material life production, in the contradictions and conflicts inherent in it.

Marx generalizes the development that produces social revolution as follows: “At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production—or what is but a legal expression for the same thing—with the property relations within which they have been at work before. From forms of development of the productive forces, these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution.”

As Marx clearly states, the driving force of social revolution and, of course, the course of history lies in the contradiction between the relations of production and the productive forces.

Here, I’ll open two parentheses related to two misunderstandings:

- The law of the conformity of relations of production to the level of development of productive forces is the fundamental law of the movement of social life. Since humans have been producing as social beings and continue to maintain this life, they have to engage in production and necessarily enter into mutual relationships for this production. This situation is the necessary determinant of human social-historical existence. These relationships are shaped according to what and how they produce. In short, this law is valid from primitive communal society to the communism of future societies. However, the law of class struggle, which assumes the existence of classes by definition, is not valid in these societies where there are no classes. The determination that history is the history of class struggles is valid in the transitional period between these two classless societies. This note is for our peculiar socialists who argue that the law of the conformity of relations of production to the level of development of productive forces is not valid during the political transition (the dictatorship of the proletariat). We suffice to remind that the problem where “Local Communisms” will get stuck in the development of productive forces and that this requires the solidarity of the developed countries of the world; otherwise, it is clear that we will fall back into the process where people strangle each other for food—the “old filth.”

- The mode of material life production conditions social, political, and intellectual life is not a one-sided process.

The political and intellectual structure also has a positive or negative effect on both the productive forces and the relations of production. In this framework, it forms a dialectical contradiction that is more backward compared to the productive forces.

For example, the Sumerians, whom Dr. Kıvılcımlı says Marx did not know, are a perfect example of this. The traditional rural-agricultural structure leads to urbanization where trade develops. Both the rural dwellers and city dwellers are Sumerians. Barbarian invasions were made not only against cities but also against Sumerian villages. While life in the villages continued in the traditional communal manner, forms of private property developed in the city, and again, the distinction and conflict between communal property and private property occurred within the same people—the Sumerians. Real dooms, that is, historical revolutions, emerge in this class distinction and conflict.

Barbarian peoples, as they settled and at the rate they adopted settled life, followed the evolutionary process of the Sumerians. Dr Kıvılcımlı derives the contradiction in a completely eclectic manner, not from the internal evolution of peoples but from separate peoples at two different historical stages. By assigning communal property to the barbarians and private property to the civilized in the distinction between communal and private property, he makes the barbarians and the civilized two opposing poles. From their conflict, he produces “Historical Revolutions.” This is the same logic that sees state capitalisms, which they call capitalism and socialism today, in an opposing, antithesis relationship. This logic saw the development of socialism in the increase in the number of countries occupied and annexed by Russia.

We have seen that the barbarians and the civilized do not form an antithesis in the way Dr. Kıvılcımlı understands it—that is, to produce historical revolutions. Similarly, the antithesis between city and countryside and between public and private property can only be formed within the same people, and only revolutions that advance history can break from this relationship.

Dr. Kıvılcımlı establishes his “Theory of History” at the point where he departs from Marxist literature and the Marxist theory of history. Dr.’s theory of history truly deserves the distinction of being “new.” In defiance of the materialist conception of history, Dr. Kıvılcımlı produces the following: “To forget the problem of barbarians, who played such a fierce role on behalf of class contradictions in history, would be not to understand ancient history.” Two conditions exist: either Marx did not understand ancient history (and essentially Engels), or Dr. Kıvılcımlı is overturning history.

After seeing that Dr. Kıvılcımlı’s “Theory of History” is a departure from Marx’s theory of history, let’s now see how he produced these errors.

HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL REVOLUTION

“In ancient civilization, a social revolution similar to that seen in modern civilization is impossible. A new social class cannot provide the collective action power to overthrow the old reactionary social class and save civilization. Then barbarian masses, who will uproot the relations of production that strangle the productive forces of the old civilization, begin to invade. Barbarians mobilize the most solid primitive socialist (tradition, custom, collective action) productive forces of prehistory. What is least found in the old civilization is especially those forces. Therefore, the old civilization cannot withstand and collapses with incredible speed. This is also a revolution(!), but since it destroys the old civilization instead of saving it, it can be called a Historical Revolution.” (p. 35)

From the first sentence to the last, everything is wrong. The first sentence is wrong because it says “a social revolution is impossible,” so the subsequent reasoning is naturally incorrect, as it is based on this faulty premise. In our view, these are wrong not only in thought but also in reality—that is, thought does not correspond to the way reality develops.

What does Dr. Kıvılcımlı base the impossibility of social revolution on? On the claim that the class capable of carrying out the revolution lacks sufficient power to overthrow the old social class. Such a productive force does not exist. More importantly, productive forces can be considered as a whole. But we will leave the discussion of this to the section where he addresses productive forces. In a social form where productive forces have not sufficiently developed, the new social class and revolutionary consciousness necessary for revolution have also not matured sufficiently. Precisely for this reason, they cannot send the old relations of production or social class to the garbage dump of history. In short, for one social class to overthrow another social class, the productive forces must reach a sufficient level of development. Why? Because “No social formation ever perishes before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have developed; and new, higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society itself.” —Marx

If social revolutions do not occur in ancient civilizations, this shows either that the class capable of carrying out the revolution has not reached sufficient maturity (for the reasons we explained above), or—as we draw the reader’s attention to the first parenthesis we opened above—the laws of the dissolution process of ancient civilizations are different. Dr Kıvılcımlı brings barbarians to the rescue of societies that could not make a social revolution. Instead of understanding their internal dissolution process, he sees an external effect as necessary for their development. Barbarians or God! On this ground, Dr. perhaps escapes idealism but falls into mechanical materialism.

For example, if Dr Kıvılcımlı had examined the Sumerians, whom he said Marx did not know, more carefully, he would have seen that class antagonism in this society is gradually developing and the possibility of a social revolution is getting closer every day. If barbarians artificially interrupt this intermediate process, it is no different from cutting down a growing tree with an ax. What remains of the tree tries to sprout again until the next cutting. Barbarian movements have such an effect on the development of civilizations. Nothing more. Dr., who claims to deepen Marx, seems unaware of these things. Worse, Marx shows that ancient and Germanic societies and modes of property are primitive communal societies that do not include the kind of class distinctions that Dr Kıvılcımlı is looking for, differing from each other due to factors such as climate, communal structure, physical conditions, etc.

“The community member’s own mode of reproduction results not in cooperation in production effort but in cooperation in the effort to protect communal (real or imaginary) interests and to maintain unity against internal and external dangers. Property is the property of the Roman citizen; Rome is property; a person can only have private property on land by being a Roman citizen; on the other hand, every Roman citizen, by this title, is a private property owner on the land.” (Grundrisse, p. 533)

“It is also understood that these conditions change. A part of the earth becomes the prey of the clans only through their hunting; it is only through agriculture that the land is made into an extension of the individual’s body. Once the Roman city is established and the surrounding lands are cultivated by city dwellers, the conditions of the community are now very different from before. The aim of all these communities is to maintain their existence—that is, to reproduce the individuals constituting the community as property owners; that is, to reproduce the individuals within the objective mode of existence that is the basis of their relationships as community members and thus of the community itself. But this reproduction necessarily involves the destruction of the old form.

For example, if every individual needs to have a few acres of land, population increase will soon intervene. To restrain this, they will engage in colonization, which will necessitate wars of conquest. Therefore, slaves…

Thus, the maintenance of the old community involves within itself the destruction of the conditions on which the community is based; it turns into its opposite. On the other hand, if we think that, with the same production—for example, through the development of productive forces—the productivity increases (which is slowest in traditional agriculture), this time this will bring new work methods, the combination of labours, and more of the population being allocated to agriculture; thus, the old economic conditions of the community will again have been eliminated.” (Grundrisse, pp. 555–556)

And finally: “In the ancient world, craftsmanship is already on the agenda as a corruption, a degeneration… The development of productive labour (beyond being limited to secondary household work, work in free time, labour solely aimed at agriculture and war, or worship; crafts employed in community services—house construction, road construction, temple construction) and its development through foreigners, slaves, work and trade, the effort to sell surplus products, etc., gnaws away from within the mode of production on which the community is based, and with it undermines the objective individual who knows no other determination than being a Roman, a Greek, etc. Exchange produces the same effect; debts, etc.” (Same book, p. 557)

This is enough. In Marx’s analyses, in the laws of the course of history, there are no barbarians. Marx shows both the development of productive forces—which he says proceeds slowly in classical land ownership—and how these societies are dissolved by the reproduction of the material conditions of their existence. Here, the point to pay attention to is that society carries its own antithesis within itself, and this emerges in the reproduction of the material existence conditions of society. This means that society evolves, or in other words, history progresses with the change of modes of production. And it has now been revealed that societies do not need an external element—like barbarian invasions—to advance or develop history, as Dr. Kıvılcımlı suggests.

Every society is divided into classes as a result of the development of productive forces. And every class division makes a social revolution in that society inevitable if there is no artificial effect that will prevent its natural development.

Dr. Kıvılcımlı, in societies that cannot make their social revolution, brings barbarians to the rescue. Their internal dissolution process could be understood, but he sees it necessary to have an external influence on their development.

HISTORY AND PRODUCTIVE FORCES

History develops through the succession of social forms replacing one another. Society develops in parallel with the development of productive forces that humans develop to transform nature for their own benefit in the struggle for survival. Although we can consider productive forces separately by abstracting them from each other, due to the internal interconnectedness of the social fabric, productive forces develop in parallel with each other. There is no society where material productive forces have developed but social structures have not. Every development of material productive forces leads to the development of human power appropriate to it and to the development of relations of production corresponding to it. Dr Kıvılcımlı imagines a civilization where material productive forces have developed but human productive forces—collectivization—have not developed. This force comes to civilizations from barbarians. Let’s see how he made this mistake.

“Classical historical materialism with a dialectical method has shown that, in any age, human society moves generally and ultimately with ‘productive forces.’ (Very well.) But attention! It has entrusted the authority to research and find exactly which ‘productive forces’ play specific roles in each age and especially in the transition stage from one age to another, according to the place and time, not to philosophy but solely and exclusively to science, based solely on events.” (p. 33)

Before getting to the main issue, let’s correct a few errors immediately. First, there is no “classical” form of dialectical and historical materialism. This worldview and method is a revolution in human thought, and more advanced forms have not yet been produced. Second, dialectical and historical materialism is not a philosophy, as everyone thinks; it is the theory of the laws of development of nature, history, and human thought. It is the only understanding that emerged in the era when human history included natural history and natural history included human history. Dr.’s emphasis here is a bad manoeuvre to strengthen himself. By suggesting that Marx did philosophy and did not show specific historical transitions, he wants to emphasize that he can fill this deficiency by doing science. Marx did not entrust these problems to anyone and solved them himself, as we have seen above.

Dr. divides productive forces into four:

- Technique: The inanimate tools and their uses that society employs in its struggle with nature—implements, equipment (tools, devices), and methods (procedures). Technique also includes work habits and experience, the method and knowledge of changing and producing.

Dr. has used “technique” to include means of production, which is incorrect. Technique, in general, is within the scope of productive forces as the mental element—that is, the production knowledge and method of humans. It is a productive force that can be considered separately from the means of production, meaning the method of using the means of production. The means of production, including production objects and tools, are another aspect.

- Geography: Defined as the material environment that surrounds society directly from the outside, or rather from within space—climate, nature, etc. The material environment that surrounds humans—climate, nature, etc.—is not a productive force. First, the term “geography” is incorrect; “nature” is more accurate. Nature, as a source of wealth, is used by Marx together with labour (Critique of the Gotha Program). However, human labour: “Labor is the source of all wealth, along with nature, which supplies it with the material it converts into wealth.” (Critique of the Gotha Program, p. 22). It follows that nature is not a productive force in itself; it is only a precondition of production and becomes a productive force only when it is the object or subject of production. In this framework, together with the tool used to transform it, it is a means of production. That is, it is an indispensable tool necessary for production. In today’s stage of production, it is more of a raw material source. Climate, of course, cannot be considered a productive force, but it is an effective element in shaping nature and humans. It is not a productive force.

- History: Defined as the spiritual environment that surrounds society directly from within, or rather from within time—tradition, remnants of customs. History is not a productive force, but it appears so from an idealistic perspective. History is what has been produced; it is a result of human actions and activities. Moreover, the Doctor refers to traditions and customs, which are the products of human production relations—the habitual relationships of interactions. If he had instead referred to the production experience accumulated by humans in the historical process in the form of production tradition (which is an important productive force technically), it could have been meaningful. The parts of human traditions and customs that include production experience are productive forces. Traditions and customs as a whole are conservative elements that often form obstacles to the development of human productive forces.

- Human: The collective action (collective activity), force and violence meaning “power,” etc., that processes both the external material environment and the internal spiritual environment of society with technical tools. (p. 33)

I really did not understand the processing of the “internal spiritual environment” of society with technical tools; the “internal spiritual” aspect he refers to—social consciousness—is not processed with technical tools. The processing of the “external material environment” of society is, of course, correct in that humans are the productive force that processes nature. If he means that, it is correct. But in this form, Dr. Kıvılcımlı defines humans as “collective action (collective activity), force and violence meaning ‘power.'” This is absolutely wrong. The reproduction of nature for their own benefit humans is through their labour power. And this power has nothing to do with violence. The production itself is social; it never has an individual character; it is the product of the relations that people necessarily enter into in the production process; social relation is also the ground on which production takes place. The productive force considered as a human is not the force that means coercion and violence but rather the ability to work and labour, which we define as the physical and mental abilities of humans. This is a capacity obtained by humans as a species in the process of humanization, by separating from animals, as a result of biological-physiological development and ultimately labour (work). Dr., with a major error, defines the collective actions of barbarian tribes as productive forces and, for this, gives such a definition of human productive force. Yet, the looting of the barbarians requires that things to be looted have been produced. Collective action is a productive force if it is carried out for production. Force and violence have a historical-social meaning only in conquests or the exploitation by states, or ultimately in the actions of the oppressed against their oppressors. These are not productive forces.

Dr.’s division of productive forces in this way is not without purpose. He bases two of the productive forces—technique and geography—on matter and the other two—history and collectivization—on humans. Since civilization lacks positive traditions and customs and collective action, it supplies fresh human power from outside, from the barbarians. “Barbarians mobilize the most solid primitive socialist (tradition, custom, collectivization) productive forces of prehistory,” he says. They overthrew the old civilization, and this is called a Historical Revolution. Dr. explains the reason for calling this a historical revolution by saying, “since it destroys the old civilization instead of saving it” and “the end of many civilizations.” Revolution is a qualitative leap. And a historical revolution should express the qualitative change in the moment of historical development. If there is no historical development, this is not a revolution. What we are talking about is the burning, destruction, and plundering of a country by another country or barbarians. This has nothing to do with revolution. Essentially, it has nothing to do with historical development. On the contrary, it is the destruction of all kinds of structures—cultural, scientific, artistic, etc.—accumulated by humanity over thousands of years. It is the interruption of the historical development of humanity by the barbarians. Dr. First metaphysically separates productive forces from each other. Then, due to the lack of these two forces (history and collectivization) in civilizations that could not make social revolutions, he brings the barbarians to their rescue.

- The productive forces of the barbarians (all of them together) are behind the productive forces of the civilizations; the productive forces of a more backward socio-economic formation do not contribute to the development of a more advanced socio-economic formation (except in terms of exploitation and looting).

- The metaphysical division of productive forces leads to major erroneous results. The collective action of barbarians arises from their collective production and technical level. This does not make them superior to civilized structures in any way. To be concrete, no barbarian tribe coming from the steppes of Asia is more advanced than the Sumerians or Hittites. In fact, we could comfortably say that if Sumer and Babylon had not been plundered by barbarians, the level of human accumulation would have been more advanced.

- For a more advanced society to reach an advanced level means that they have developed and surpassed the productive forces carried by the barbarians. Naturally, for the development of societies, it is also necessary to develop their given productive forces. Otherwise, the old “productive forces” they have surpassed (Dr. also says that the civilized once had the collective action force they now need) have no benefit in the development of society. Historically surpassed is what has become unnecessary in the social production of humans. The changing and developing needs of humans are the motor of the development of productive forces. A technique or tool that is no longer useful in meeting needs is set aside; of course, replaced with a new, developed one.

FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE BARBARIANS

- These attacks are, first and foremost, unilateral and come from barbarians.

- These attacks stem from the migrations of the barbarians, from the natural necessity of the barbarians’ production and living conditions (which are also a product of circumstances). Contrary to what Dr. Kıvılcımlı assumed, these migrations are not due to the development of the barbarians’ human productive forces but to their primitiveness. These migrations arose due to population growth, the need for more food, changes in climate zones, the necessity of raising more animals on less land, and consequently, the need for more land.

- All of this caused small and large migrations to occur periodically. It is very clear that the barbarians did not begin these migrations because the civilized peoples invited them, but rather despite them, driven by their internal contradictions.

INSTEAD OF A CONCLUSION

- Barbarian movements are not the dialectical force driving the development of history but are merely horizontal, mechanical, mass movements.

- Their consequences include the plundering of many countries and the destruction of many states. In other words, they have had destructive effects on social and political structures. They have had no impact on the development of productive forces or on social revolutions. On the contrary, they led to the destruction of the productive forces developed by civilized peoples over hundreds of years, thus causing humanity’s history to regress or pause temporarily.

- Therefore, no antithesis relationship between the civilized and the barbarians would drive the engine of historical development. Moreover, Dr. Kıvılcımlı considered the barbarians to be the revolutionary element that moved and developed history, which is completely absurd.

- Hence, these “catastrophes” are not the necessities arising from dialectical contradictions, but the coincidental encounters of societies — in this case, the barbarians — with external elements under the determination of their internal necessities. These barbarian invasions are comparable to a starving predator stumbling upon a herd of deer while wandering the steppes and attacking them. Moreover, these are not coincidences that benefit the deer or the civilized peoples. In the end, there is the plunder of countries that had reached a certain level of development and were on the brink of significant leaps, and often the destruction of productive forces. External wars, or wars between countries, always destroy productive forces. In history, only the wars of oppressed classes and peoples against the ruling classes and states are revolutionary. These are the wars that accelerate historical-social development and produce revolutionary results.

- The development of productive forces and social revolutions (that is, the replacement of a backward mode of production with a more advanced one, and the transformation of social structures) are the sole sources of human historical progress. Outside of social revolutions, there is no separate “historical revolution.” Dr. Kıvılcımlı formulated his thesis without being aware of Marx’s Grundrisse. After becoming aware of it, he fell into dogmatism by not revising his thesis. However, the primary dogmatism was not produced by Dr Kıvılcımlı himself but by his followers, who, despite all the scientific advancements, continue to present his books and ideas to us in a dogmatic manner without any critical annotation. Dr. Hikmet Kıvılcımlı’s effort is undoubtedly a bold one and can be appreciated. But we have also seen what a slight deviation from the Marxist understanding of history can lead to. The task of contemporary Marxists is not to repeat old texts dogmatically but to continuously reproduce the internal connections of objective developments, the concrete totality, and historical context in thought — in other words, as science.

Key reference:

- Marx, Karl, and Engels, Friedrich. The German Ideology. Progress Publishers, 1976. This text outlines the foundation of historical materialism and critiques the idealist philosophies of history.

- Engels, Friedrich. Dialectics of Nature. Progress Publishers, 1976. Engels discusses the application of dialectics in nature, a key text in the Marxist philosophy of science.

- Kıvılcımlı, Hikmet. The Theory of History. A review of Kıvılcımlı’s application of Marxist theory to history reveals the limitations of his approach and its reliance on mechanical causality.

- Marx, Karl. Capital: Volume I. Penguin Classics, 1990. Marx explains the dialectical evolution of society through labour and class struggle.

- Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species. John Murray, 1859. Darwin’s work on biological evolution provides a framework for understanding human evolution.

- Marx, Karl. The Communist Manifesto. Marx/Engels Selected Works. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1958. This foundational text argues that history is the history of class struggle.

- Comte, Auguste. The Course in Positive Philosophy. 1830-1842. Comte’s positivism emphasizes empirical observation, which is critiqued in Marxist theory.

- Althusser, Louis. For Marx. Verso, 2005. Althusser critiques the reduction of Marxism to a mere empirical science and argues for its revolutionary potential.

Footnotes:

- Marx, Karl, and Engels, Friedrich. The German Ideology. Progress Publishers, 1976, p. 47.

- Engels, Friedrich. Dialectics of Nature. Progress Publishers, 1976, p. 17.

- Kıvılcımlı, Hikmet. The Theory of History. [Publisher and year, if available].

- Marx, Karl. Capital: Volume I. Penguin Classics, 1990, p. 73.

- Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species. John Murray, 1859, p. 65.

- Marx, Karl. The Communist Manifesto. Marx/Engels Selected Works. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1958, p. 34.

- Comte, Auguste. The Course in Positive Philosophy. 1830-1842, p. 92.

- Althusser, Louis. For Marx. Verso, 2005, p. 155.

Review

88%

Summary In this text, Şahin critiques Dr. Hikmet Kıvılcımlı's Theory of History, arguing that Kıvılcımlı's concept of "historical revolutions," driven by barbarian invasions, is flawed. Şahin states that these invasions were not revolutionary but destructive and did not contribute to the progress of productive forces or the development of societies. Instead, he asserts that true historical progress is driven by internal class conflicts and social revolutions within societies, as described by Marxist theory.Şahin emphasizes that civilizations develop through the dialectical process of internal contradictions between productive forces and relations of production. He believes that Kıvılcımlı's reliance on external barbarian forces as drivers of historical change overlooks the central role of internal social dynamics. He also argues that Kıvılcımlı's theory deviates from Marxist principles and falls into mechanical materialism by misunderstanding the nature of social revolutions.In essence, Şahin’s critique reinforces the Marxist view that historical development stems from internal, dialectical contradictions within societies, not from external forces like barbarian invasions. He also stresses the importance of continuously updating Marxism with new scientific data while maintaining its foundational principles.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks