Ismet Sahin: Thought and Philosophy

SME SAhIn: Thought and Philosophy

İsmet Şahin (Turkish pronunciation: [ismet ʃahin]; born 01 February 1969) is a Turkish thinker:[1], author[2][3], publisher[4], politician[5],and ultramarathon runner[6]. İsmet was influenced by Aristotle, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx. He has been a strong proponent of Marxism, right up to the book The Child Escaped the Classroom, which is a critique of Marxism as a whole. He always refers to Aristotle, [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel|Hegel and Marx as his masters. However, he likens his position to that of Aristotle before Plato and Marx against Hegel. Like classical philosophers, he has worked with all his might to solve every problem that humanity puts before it. Under the captivity of time, he was only able to work on certain subjects. He has done deep research in almost every field of philosophy. But especially the history of science and philosophy were the topics that attracted his attention the most. Along with only studies of quantum physics, philosophy of science and especially philosophy of physics became an area where he concentrated. Starting from his high school years, İsmet Şahin conducted and published a wide range of scientific studies, mostly in the field of philosophy, from politics to social sciences, from workers’ rights to the rights of oppressed nations, from the history of science to philosophy of science, from economy to global capitalism. İsmet Şahin was not content with only theoretical studies. He has been active in politics all his life, starting with his high school years. He published and directed many political newspapers. Furthermore, he became an independent parliamentary candidate a few times, but never succeeded in being elected. İsmet Şahin focused on the philosophy of physics after coming to terms with his own past theory, Marxism. He is currently working on the philosophy of science, the history of science, and the philosophy of quantum physics.

Born February 1, 1969

Osmaniye, Artvin, Turkey🏳️ Nationality  Turkey

Turkey🏫 Education 💼 Occupation 🏢 Organization Praksis Publishing and Praksis Magazine (since 1996). Artvin Ultra Trail (2017-2018) Notable work Anti Kapitalist Manifest, Sınıftan Kaçan Çocuk, Quantum Filozofi Predecessor Aristoteles, Hegel, Marx Movement Libertarian, Contemporary Philosophy, There is no closed whole: New understanding of history, society, economics, epistemology and politics,

Atheist

👩 Spouse(s) Married 1991–divorsed 2000 👶 Children Deniz Şahin İsmet Şahin was born on 1 February 1969 in Osmaniye village, located in the Kemalpaşa district of Artvin Province, in the northern part of Turkey. He was the fourth of five children, with three sisters and two brothers.

Ismet’s formative years were spent in a family engaged in tea cultivation and sheep farming, a period marked by a significant transition in their livelihood. At the age of six, his family relocated to Aydinlikevler in Ankara, where he commenced his primary school education at Aydinlikevler Primary School. He subsequently pursued his studies at Mehmet Akif Secondary School and Aydinlikevler High School.

In 1988, Ismet Şahin commenced his studies at Hacettepe University, enrolling in the Department of Philosophy. However, his academic career was brought to an abrupt end in 1991 as a consequence of his involvement in political activities, which resulted in his detention and subsequent expulsion from the university.

During this period, Ismet entered into a marital union with his university partner in 1991. They subsequently relocated to Istanbul, where they subsequently had a son, Deniz, in 1997. The couple divorced in 2000, after which Ismet returned to Ankara.

In 2012, Şahin was granted amnesty and permitted to resume his studies at Hacettepe University. He graduated in 2014 with a thesis focusing on the Philosophy of Science.

Ismet Şahin currently resides in Ankara with his son. During the summer months, he resides in Kemalpaşa, where he engages in tea farming, which constitutes the primary source of his income. He continues to earn the majority of his income through tea farming, reflecting his strong connection to his roots.

İsmet Şahin’s Political Philosophy: Radical Change and Social-Economic Justice

Ismet Şahin’s political vision represents a compelling argument for transformative change and social justice. His approach challenges the established political and economic systems, advocating for a society that prioritises equality, fairness, and human dignity. At the core of Şahin’s vision lies the conviction that genuine progress can only be attained by challenging and transforming the prevailing structures of power, including capitalism, to foster a more inclusive and just society.

A central tenet of his philosophy is the concept of radical transformation. According to Şahin, incremental reforms are inadequate for addressing the deeply entrenched social injustices. Instead, he proposes a comprehensive restructuring of the social, political, and economic systems that perpetuate inequality. Such issues as wealth disparity, access to education, healthcare and the protection of human rights, particularly for marginalised communities, must also be addressed.

Additionally, Şahin’s political stance is intertwined with his philosophical views, which draw on radical critique to explore the necessity of reshaping societal norms and values. His philosophy posits a return to the fundamental principles of justice and equality, which should inform not only political movements but also everyday life.

From this perspective, İsmet Şahin’s political vision extends beyond mere policy change; it encompasses a radical transformation in the collective consciousness of society. The transformation he envisions extends beyond political action, aiming to inspire a philosophical reimagining of what it means to live in a just society. By combining a call for political change with a deep philosophical commitment to justice, Ismet Şahin’s political vision offers a comprehensive framework for addressing the systemic issues that continue to shape the modern world.

İsmet Şahin is among the generation of individuals who played a pivotal role in organizing the inaugural political freedom activity following the September 12 military coup. Ismet initiated his political activities at an early age, participating in the socialist movement in Ankara. He initiated his political activities at the journal Gökyüzü, which commenced publication in 1984 at the age of 15. He participated in the founding convention of the Socialist Party at the İnci cinema in Istanbul Beşiktaş. He delivered the speech on behalf of the younger members of the group.

Subsequently, he proceeded to engage in further activities within the socialist political milieu designated as Kurtuluş (KSD). In 1987, he published Liseli Genç magazine, which served as the official publication of Devlis. Additionally, he played a role in the establishment of Yeni Aşama, Yeni Öncü magazines and the newspaper İşçi Dünyası. Until 1991, he fulfilled a variety of roles at different levels within the same political structure.

In 1991, following a series of discussions concerning the potential for a separate organisation of Kurdish workers, the structure of democratic mass organisations, the class character of the USSR, and the challenges of revolution and organisation, he departed from Kurtuluş and established a new political structure in collaboration with his colleagues.

At the age of 21, he was detained in 1990 for establishing and administering the organisation known as Communist Worker. The defendants were tried and acquitted due to a lack of evidence. He was a member of the editorial board of the journal Socialist Worker, which commenced publication in 1992, and the Journals of Workers and Politics. In 1996, he published the journal Praksis. Furthermore, he established the Praksis publishing house. He served as the editor-in-chief of the Sokak newspaper, which commenced publication at the end of 1996. Additionally, he has been responsible for the publication of the Street Newspaper for one year. In 2001, he assumed responsibility for the publication of the Communist Worker newspaper. Concurrently, he published a collection entitled Imperialism and a pamphlet entitled Why Marxism is Against Terrorism.

In 2006, while they were engaged in ongoing political and theoretical work as the Praksis circle, they accepted an invitation from the Democratic Society Party (DTP) to contribute to the Turkishisation efforts of Turkish intellectuals. It participates in the DTP administration. In the 2007 general elections, he stood as the common left-wing candidate for the position of Independent Deputy for Bin Umut in Balıkesir. After the electoral process, he departed from the aforementioned political party and resumed his independent scientific pursuits.

Subsequently, İsmet Şahin became an independent parliamentary candidate representing the 2nd district of Istanbul in all subsequent elections.

In the 2018 Turkish presidential elections, İsmet announced his candidacy. However, he was unable to meet the financial requirements for candidacy, namely the sum of 130 thousand TL, and thus was unable to pursue the candidacy.

İsmet Şahin A Passion for Athletics and Ultra-Marathons that has Ruled His Life from Childhood to the Present Day

İsmet Şahin commenced his athletic career at the tender age of 11 when he enrolled in the 100-metre sprint. In 1981, he was accepted into the Yıl Sports School in Ankara. From this early introduction to sports, his passion for running developed into a lifelong commitment, particularly in the disciplines of marathon and ultra-marathon running. Throughout his career, he has participated in a multitude of races in Turkey and abroad, exemplifying not only his physical endurance but also his mental resilience.

Over the past 13 years, Şahin has focused his attention on ultra-marathons, challenging the limits of human endurance in races that extend beyond the conventional marathon distance of 42.195 kilometres (26.2 miles). His longest recorded ultra-marathon distance is an impressive 110 kilometres, which serves as a testament to his remarkable physical and mental resilience. These races frequently occur in challenging environments, such as trails and mountainous terrain, necessitating rigorous preparation and adaptability.

Notable among his achievements is his participation in the White Nights Marathon in St. Petersburg, which is renowned for its challenging conditions and scenic route. His achievements in this and other races, including the Nashira Ultra, İznik Ultra, Sapanca Ultra, Antalya Ultra, and the Cappadocia Ultra, have resulted in the acquisition of numerous medals, thereby establishing his reputation as a dedicated and accomplished runner on the international stage.

In addition to his role as a competitor, Şahin has made significant contributions to the global trail-running community as a member of the International Trail Running Association (ITRA). His expertise and passion for ultra-running led him to organise the Artvin Ultra Trail, an international ultra-marathon event held in 2017 and 2018 in the Artvin region of Turkey. The races attracted participants from around the globe, underscoring both the area’s natural splendour and Şahin’s leadership within the ultra-marathon community.

Ismet Şahin’s dual role as both an athlete and an organiser reflects his profound comprehension of the sport, not merely as a vehicle for personal accomplishment but as a means of uniting runners and advancing endurance athletics on a global scale. His career in ultra-marathons serves as an exemplar of his enduring dedication to transcending physical and mental limitations, resonating with his broader philosophical perspective on life and human potential.

Thought and Philosophy

Background of Ismet’s Philosophy

As can be understood from his writings, İsmet Şahin had a classical Marxist perspective in his early political periods. He wrote, his own book Anti-Capitalist Manifesto[3]

“Historians of the human societies of the future will say, “they were not human” when evaluating the people of today. This phrase, which Engels used to describe the situation of the working class in England, where capitalism first appeared on the stage of history, has now been realized by including the whole world. The four hundred years of development of capitalism have brought nothing but intensifying the exploitation of the working classes throughout history. But for the first time, the workers, who are held captive by this relationship of exploitation, have obtained the objective historical conditions that will save the entire society along with them.

While capitalism paved the way for the salvation of all humanity with the “gravediggers” it created, it also established the most barbaric relationship of exploitation in the history of all humanity. To perpetuate this barbarism, capitalism has massacred millions of people in two worlds and hundreds of local wars. Although many wars are going on today, countries spend nearly half of their budgets on military investments to continue the exploitation of their own lands and other peoples of the world. The US alone spends $800 billion, twice as much as the rest of the world spends on arms. Even a single example is enough to show the extent of the exaggeration in armament.

The price of B2, Stealth bombers, is $2.3 billion.[13] It is the most expensive fighter aircraft ever built. Each plane is worth three times the value of its own weight of gold. But in the United States, the poorest 20% of the population is poorer than the poorest 20% of Egypt, India, Argentina, and Indonesia.[14] The fact that every daring revolt of the working class against the abolition of these exploitative relations, in individual countries and the world as a whole, results in defeat, leads to a further riveting of the barbarity of capitalism. The continuation of this hegemony of barbarism will justify historians of human society.

Roughly speaking, saying that determinism supports socialism would rather be a crude, fatalistic interpretation of Marxism. The historical necessity stated by Marx includes the counterforce that the working class will undertake. Capitalist barbarism will continue to exist as long as the working class and the oppressed do not appear on the stage of history in order not to be ruled and to rule themselves. It is clear that history is created by the classes that mark their course.

Barbarism continues its exploitation by reproducing itself at the economic, political and ideological levels. It does not hesitate to use its militarist forces whenever this reproduction is in danger. But capitalism is not just an instrument of military repression. Capitalism has spontaneity and therefore an ease that attracts the individuals within it. In daily life, if the individual is not equipped enough, he easily surrenders himself to objectivity, to the yoke of capitalism. Humanization efforts and thoughts of individuals require a consciousness, will and a continuous activity fed from them. Marxism is the scientific guide of the individual who desires emancipation.

While Marxism demonstrates to the working class the ways to save the society as a whole, along with itself, it also shows the individual that the guarantee of his salvation lies in the participation of the working class in this historical action. The liberation of the individual is his participation in his transformation with the consciousness of history.”[3] “The coincidence of change or self-change of circumstances and human activity can only be grasped and understood rationally and through revolutionized practice”.[15] (Marx)

An abstract of the philosophy of İsmet Şahin

Emancipation of Individual

İsmet Şahin’s book, which also has a reckoning with his own theory of the past, in which Marx developed a completely different theoretical perspective of many fundamental subjects such as history, dialectical method, class struggle, critique of capitalism and understanding of science: Sınıftan Kaçan Çocuk

“No form of Marxism has consistently solved the problem of individual freedom. More than that, it has placed the individual under the determination of organisation, society, class, state and ideology. The individual is only a class-determined element in Marxism.

The emancipation of the individual is constantly postponed to the “other world”, to the supposedly coming social order, to the hoped-for “golden age” on the Christian model. For this reason, all kinds of demands are made not for individual freedoms, but directly for the freedom of the class. The individual will attain these freedoms as a member of the class. The freedom of the individual is mediated by social structures. Therefore, the individual can easily be sacrificed in favour of a class and a country.

However, if you open the freedom spaces of the individual, you will see that the whole society will be liberated by itself. It can be seen that the traditions of Marxism could not break away from the scientific paradigm of the 19th century and were shaped by the completely negative political environment of the Cold War period. Therefore, they relate the emancipation of the individual to the socialist society that will emerge through the collective action of the working class, i.e. to the future paradise. For this reason, they cannot give an answer to the problem of the freedom of the individual in the present.[2]

History and Class Struggle

I place state-dependent relations alongside human-dependent relations and commodity-dependent relations. By state-dependent relations, I mean that states are the main component in the reproductive processes of societies, the main variable of the function called history. So in the context of class warfare, history is not the product of two classes, two variants of those who wage this war. History is the product of a matrix of infinite variables. And when we explore these variables, we make history and social science.[2]

Human Emancipation and Globalization Momentum of Capitalism

Globalisation, the realisation of the production process of a commodity on a global scale, bringing the intellectual capacities and perspective of human beings to the global level, is the most advanced stage of humanity so far in terms of social forms. It has created real material and cognitive possibilities for the liberation of the individual. It has liberated the individual and thus societies from the constraints of time and space. All the possibilities of human emancipation have been revealed.”[2]

Escaping Class: A Philosophical Critique of Marxism

The conference “Marx, Marxisms and Freedom”

Escaping Class: A Philosophical Critique of Marxism

Overview

Escaping Class: A Philosophical Critique of Marxism is a scholarly work authored by İsmet Şahin, reflecting a radically changed theoretical perspective on core dimensions of Marxist theory. While firmly grounded in a critical reassessment of Karl Marx’s foundational concepts—history, dialectical method, class struggle, critique of capitalism, and scientific inquiry—this volume ultimately proposes completely different theoretical perspectives relative to conventional Marxist readings.

These perspectives were shaped by years of intellectual evolution. The book openly acknowledges that the author’s viewpoint diverged significantly from traditional Marxist understandings, resulting in deeper theoretical insights into Marx’s methodology, the role of class, and the tension between collective liberation and immediate personal freedom.

First aired in a public venue at the “Marx, Marxisms and Freedom” conference organized on November 8–9, 2012, by the Department of Economics (English) at Hacettepe University, Escaping Class capitalizes on earlier editorial work in Praksis magazine (launched in 1996). While building upon Marx’s corpus—especially Capital (Volume I, Volume II, and Volume III)—Ismet Şahin argues that the interpretive issues do not lie solely in Marx’s or Engels’s original formulations but in how “Marxism” has historically been understood and politically implemented.

Beyond a mere reinterpretation of Marx, the book posits an entirely new standpoint, reflecting the author’s changed theoretical outlook. This vantage underpins a critique of conventional 19th-century social theories, and a bold call for a renewed approach to questions of dialectical materialism, class primacy, and the scientific method in social analysis. In so doing, it invites readers to move away from dogmatic readings and embrace a more flexible, contingent, and freedom-oriented perspective on Marxist thought.

Structure and Themes

Following a short Introduction, the book is divided into six major topical chapters with a concluding footnote apparatus:

- The Concept of Class in Marx’s Method

- Does Marx Have a Method?

- Marx’s Method

- A Concept of “Class” and “Classification”

- The Formation of the Concept of Class in Marx

- Marxisms and Individual Freedom

- A) Stalinism

- B) Trotskyism

- C) Western Marxism

An extensive Footnotes section provides both primary source references (e.g., from Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, and various historical documents) and secondary commentaries (e.g., R. Rosdolsky’s analysis of Capital, older conferences, and editorial commentary from Praksis).

Introduction

In the Introduction, İsmet Şahin recounts how the “Marx, Marxisms and Freedom” conference (November 8–9, 2012) furnished the first public platform for presenting his radically altered viewpoint on Marxist methodology. Having laid the foundations in 1996 via his work in Praksis, Şahin underscores that while early on he might have adhered to a more classical Marxist orientation, over time he recognized deeper problems within the tradition. These concerned:

- History: The assumption that progress is linear, culminating inevitably in socialism.

- Dialectical Method: The conflation of Hegel’s dialectic with a universal, cosmic law known as “dialectical materialism.”

- Class Struggle: The widespread Marxist notion that “class” is the supreme category dominating all social and historical processes.

- Critique of Capitalism: The standard Marxist reading of capitalism as wholly determined by the capitalist-labor antagonism.

- Philosophy of Science: The potential dogmatism that arises when “dialectics” is treated as an absolute worldview, immune to empirical anomalies.

The Introduction also clarifies that Escaping Class is not intended as a comprehensive manual for a new “system,” but as an initial text encouraging an open-minded, contemporary scientific approach free from 19th-century prejudices. It signals a radical shift in how Marx’s thought could be understood, moving away from entrenched positions that overshadow the role of individual freedom.

1. The Concept of Class in Marx’s Method

1.1 Rethinking Marx’s Priorities

Chapter 1 posits that Marx’s method cannot be boiled down to a single overarching concept, least of all “class.” The author’s changed perspective originates here, observing that while standard Marxist readings often elevate class as the universal key to decipher historical movement, Marx’s own texts reflect a more multi-faceted approach. Concepts such as commodity, value, capital, and surplus value each play critical roles in his theoretical architecture.

1.2 Concrete vs. Abstract Concepts

In Capital and other writings, Marx systematically organizes concepts from “simpler” to “more complex.” Within this framework, class appears concrete relative to categories like labor or capital but remains abstract relative to categories that presuppose it. Therefore, from the vantage of the text, class is “one of the concepts” in Marx’s conceptual system, not a privileged or dominating one. Historically, however, Marxists (particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries) politicized the role of class, conflating method with activism.

1.3 Political vs. Scientific

By highlighting the difference between political mobilization (the manifesto style of “Workers of the world, unite!”) and analytical rigor (the systematic exposition in Capital), Escaping Class confirms that while class is significant, it does not exercise unilateral primacy. This nuance is crucial for understanding the advanced perspective espoused by İsmet Şahin, who holds that the mismatch between Marx’s multi-varied analysis and Marxist dogma about class leads to theoretical distortions.

2. Does Marx Have a Method?

2.1 The Controversy Over Dialectical Materialism

Chapter 2 takes up a fundamental query: “Does Marx truly possess a unified method?” If so, is it properly named “dialectical materialism,” or is that an imposition by later interpreters—most notably Friedrich Engels and subsequent Soviet thinkers?

- Traditional groups, especially dogmatic left circles, treat dialectical materialism as the science and philosophy of Marxism.

- Western Marxism (e.g., Lukács, Korsch, Althusser) often question whether the term arises from Marx or from Plekhanov’s and Engels’s expansions.

- Marx rarely or never wrote “dialectical materialism” side by side in his published texts.

Ismet Şahin’s changed stance here reveals that focusing too narrowly on “dialectical materialism” obscures the more fluid, partial, and open-ended nature of Marx’s approach. Indeed, while Marx insisted he would strip Hegel’s dialectic of its “mystical shell,” the project was never completed in a definitive treatise. Lenin and many later Marxists, by contrast, systematically codified “dialectical materialism” into a near-complete worldview, as in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1909) or Stalin’s writings on Marxism–Leninism.

2.2 Synthesis of Feuerbach and Hegel

A central claim is that Marx’s philosophical stance is a synthesis of Ludwig Feuerbach’s materialism (itself not entirely endorsed by Marx) and Hegel’s dialectics, used non-dogmatically to interpret historical changes. Materialism here implies that reality exists independent of human perception, while dialectics denotes the dynamic, contradictory processes driving change. Yet the text contends that “dialectical materialism,” as a fixed label, does not appear in Marx’s own usage. Instead, it arises from subsequent expansions (especially by Engels and Soviet Marxists) that rendered dialectics a universal law of nature.

2.3 Mystical Shell Freed?

Marx famously alludes to the “mystical shell” that must be stripped away from Hegel’s dialectic. For the author, the question is whether that shell was truly removed or whether subsequent Marxists inadvertently re-mystified the dialectic by rendering it absolute. From the vantage of İsmet Şahin’s revised viewpoint, the real problem was not Marx’s original statements but the solidification of “dialectical materialism” into a dogma. This hardened approach neither does justice to Hegel’s subtleties nor to Marx’s open-ended historical inquiries.

3. Marx’s Method

3.1 Philosophical Materialism Meets Hegel

Chapter 3 explores how Marx’s method in Capital entailed a critical philosophical materialism joined to a Hegelian style of conceptual development. Independently of Hegel, classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo used a deductive method from the general to the particular. Marx recognized their breakthroughs but contended they did not push their abstractions to their logical ends, leading them to incomplete conclusions. This reflection parallels the changed stance in Escaping Class, which recognizes that Marx was an heir to classical political economy but not exclusively bound by its rules.

3.2 Method of Inquiry vs. Method of Presentation

Crucially, the text references the distinction between:

- Method of Inquiry: Investigating the real, concrete phenomena in history, economics, and society.

- Method of Presentation: Organizing these findings into coherent, logical forms, from abstract simplest concepts (e.g., commodity) to the complexity of a social totality (capital, surplus value, etc.).

This approach in Capital resonates with Hegelian logic but is re-grounded in materialist investigations. Yet, the text notes the tension in Capital’s first chapter, where Marx’s retelling of how a product becomes a commodity is partly historical, partly conceptual, not purely deducing from an abstract principle. From the vantage of the author’s new perspective, we see that class itself is not singled out as the “alpha and omega” of Marx’s system, even if mainstream Marxism advanced a more monolithic reading.

3.3 Implications for “Class Struggle Is All of History”

One upshot is that if no single category (including class) monopolizes Marx’s method, we cannot reduce history to “the history of class struggles” in a purely scientific sense. Rather, Marx’s method includes numerous dimensions—commodity production, surplus value extraction, capital accumulation, and political power. Class is merely one layer. This partly explains why, from Ismet Şahin’s standpoint, a reevaluation was necessary: the dogmatic acceptance of “class” as the ultimate lens overshadowed a more nuanced reading of Marx’s manifold interests, including individual autonomy in immediate social processes.

4. A Concept of “Class” and “Classification”

4.1 Pre-Marxian Philosophies of Class

Chapter 4 reviews how the notion of classification is as old as recorded history. From Plato’s three-class schema (guardians, auxiliaries, producers) to Aristotle’s systematic classification in ethics and biology, humans have always grouped objects or persons by shared properties. In modern social science, “class” becomes a major axis of classification, overshadowing older terms like estate, caste, or rank.

4.2 Marx’s Historical Inheritance

Marx openly acknowledged that he was not the first to discover the existence of classes or their conflicts. Previous historians, such as those analyzing feudal societies or the English Revolution, had recognized class-like antagonisms. The novelty is that Marx invests the working class (the proletariat) with the historical mission of overturning capitalism, ultimately dissolving class divisions. The text clarifies that this mission is not purely scientific but also normative and political.

4.3 Modern Social Sciences

Hence, for an advanced, scientific approach, it is key to see how “class” fits into the broader tradition of classification in social sciences. That classification might revolve around property ownership, social status, political consciousness, or forms of exploitation. Marx’s own usage (in The Eighteenth Brumaire, The Poverty of Philosophy, etc.) underscores how class is as much a socio-political category as an economic one—hence it cannot be pinned down unilaterally.

5. The Formation of the Concept of Class in Marx

5.1 From Generic Conflicts to Emancipatory Class Struggle

Chapter 5 shows how Marx’s originality is not in discovering that classes exist, but in forging the link between class conflict and a future emancipation from all classes. In an advanced, scientific sense, this means that while class predates Marx, the Marxian viewpoint (especially in The Communist Manifesto) invests class struggle with a decisive, revolutionary outcome—namely, the ascendancy of the proletariat and the abolition of class divisions.

5.2 Weydemeyer’s Letter and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat

A pivotal moment is Marx’s letter to Joseph Weydemeyer, dated March 5, 1852, in which Marx enumerates three key ideas he claims as distinctive:

- Classes are tied to historical phases of production.

- Class struggle leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat.

- That dictatorship is itself transitional to a classless society.

Yet, the text cautions that real historical attempts to realize this outcome (e.g., the Soviet Union after 1917) complicated these neat categories. Within the changed perspective that Ismet Şahin now advances, the text scrutinizes how classical Marxism might overemphasize the inevitability of this transition while underestimating contingency, power, and individual liberties.

5.3 Ambiguities in Capital

Finally, the author notes that Marx never completed a fully systematic statement of how classes concretely line up in capitalism. The concluding pages of Capital, Volume III are famously incomplete, leaving future Marxists to extrapolate from partial outlines. This textual gap partly explains the divergences among Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Rosa Luxemburg, and later Marxists. From the vantage of Escaping Class, it also shows that class in Marx is historically fluid, further supporting the author’s argument that the enthronement of “class” as an absolute principle was more ideological than textual.

6. Marxisms and Individual Freedom

6.1 Why Individual Freedom is Central

Chapter 6 shifts to a decisive topic: the place of personal and individual liberty in Marxism. It begins with Marx’s quip “I am not a Marxist,” signifying his discomfort with the rigid codification of his ideas. Ismet Şahin’s newly evolved perspective places immediate personal freedom at the center of the critique, asserting that classical Marxism—whether Stalinist, Trotskyist, or Western—postpones or subordinates individuals’ rights in favor of class victory or structural transformation. This postponement, the author argues, is deeply problematic.

Below, the text examines three major currents:

(A) Stalinism

A1. The October Revolution and Worker Soviets

The section on Stalinism highlights the transition from early 1917 worker control (Soviets, factory committees, etc.) to the bureaucratic system under Stalin. Initially, Bolshevik principles included wage equality for officials, election and recall of bureaucrats, and mass involvement of workers in management—mirroring aspects of the Paris Commune (1871). However, by the late 1920s, single-person management, top-down directives, and forced labor overshadowed those ideals.

A2. Competition, Restrictive Policies, and Forced Labor

Stalin’s industrial drive, symbolized by the Five-Year Plans, enforced worker competition through piece-rate wages, effectively undermining solidarity. At the same time, reintroduced internal passports tied workers to specific localities, threatening penalties for leaving or absenteeism. Freedoms guaranteed in the 1922 Labor Code—especially for women—were eroded once the regime demanded mass labor in mines and heavy industry, dismissing previous protective measures. The Gulag system expanded rapidly, capturing millions.

A3. Subordination of Consumption, Growing Inequality, and State Capitalism

Production was geared toward heavy industry and militarization; real wages often dropped, while the bureaucratic elite (or nomenklatura) achieved new privileges, rewriting the principle of equality so central to early Bolshevik hopes. This scenario is labeled “bureaucratic state capitalism,” merging central planning with integration into global markets. Personal freedom (the right to move, to choose occupations, to express dissent) was systematically curtailed.

A4. Engels, Lenin, and Premature Revolutions

The text alludes to Friedrich Engels’s caution (in The Peasant War in Germany) that revolutionaries forced to take power prematurely may betray their own class. Similarly, Vladimir Lenin had foreseen that, absent a German revolution, the Soviet experiment might fail. Historical isolation, combined with Stalin’s leadership, produced forced industrialization at the expense of workers’ freedoms, confirming the text’s argument that under Stalinism, individual rights were postponed indefinitely in favor of “building socialism.”

(B) Trotskyism

B1. A Different Revolution, Yet Parallel Framework

Leon Trotsky parted ways with Stalin over the bureaucratic degenerations of the Soviet state but retained the fundamental assumption that a dictatorship of the proletariat might suppress certain freedoms until “true socialism” prevailed. Trotsky’s role in the violent suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion (1921) is emblematic. He insisted on militarizing labor, particularly during the civil war, subordinating personal choice to class necessity.

B2. Critique but No Real Guarantee of Freedom

While Trotskyism proclaims itself more faithful to Marx’s revolutionary impetus, Escaping Class argues that it never fully resolves the tension between collective discipline and individual liberty. Thus, from the standpoint of Ismet Şahin’s new perspective, Trotsky’s condemnation of Stalin is accurate in diagnosing bureaucratic tyranny but fails to erect any robust structure for personal rights in the present. Instead, it defers freedom to a future world revolution.

(C) Western Marxism

C1. Negative Dialectics and the Culture Industry

Western Marxism—as seen in Antonio Gramsci’s notion of hegemony, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s Frankfurt School critique of mass culture, and Herbert Marcuse’s “one-dimensional man” analysis—addresses forms of alienation and manipulation in advanced capitalist societies. However, these thinkers rarely provide a constructive or immediate path for personal liberation short of general social upheaval.

C2. Historical Context: Fascism, Stalinism, and Defeated Revolutions

The reasons behind Western Marxism’s negativity lie partly in the catastrophic events of the early-to-mid 20th century: the failed German Revolution of 1918–19, the rise of fascism, and the disillusionment with Stalinism. The text shows that Western Marxists replaced direct organizational imperatives with intellectual critique but seldom overcame the deeper Marxist premise that “real freedom” awaits a future structural transformation.

C3. The Issue of Immediate Freedoms

Hence, while Western Marxists might have criticized Stalin or championed critical reason, they did not robustly incorporate immediate personal freedoms into their frameworks. This parallels the viewpoint of Escaping Class, which contends that deferring individual rights or autonomy runs through all major Marxist traditions, failing to produce an actual blueprint for how to secure liberty in the present.

İsmet Şahin’s Radically Changed Perspective

A distinctive feature of Escaping Class is İsmet Şahin’s acknowledgment that his stance diverged from earlier convictions. Drawing upon experiences from the Praksis editorial collective and subsequent deep reflections, the author confesses that an initial endorsement of classical Marxist themes gradually gave way to fresh insights:

- History: Not a linear transition from feudalism to capitalism to socialism, but a complex, contingent interplay of many forces.

- Dialectical Method: More fluid, partial, and historically situated, rather than an absolute cosmic law known as “dialectical materialism.”

- Class Struggle: Political slogans such as “The history of society is the history of class struggles” reflect rhetorical mobilizations more than strictly scientific truths; other socio-historical dynamics, like technology, the state, identity, or chance, can also shape outcomes.

- Critique of Capitalism: While capitalism remains exploitative, a narrower “capital vs. labor” lens can miss multiple forms of oppression not always coextensive with class—this includes patriarchy, racism, and cultural hegemony.

- Understanding of Science: Ties in with a more open, contemporary approach to method, possibly integrating post-19th-century scientific developments (like complexity theory or new epistemological frameworks), thus departing from mechanical or dogmatic “dialectical materialism.”

By the end of the text, the author’s “radical change” is fully manifested: Escaping Class does not simply refine old arguments but completely reshapes one’s understanding of Marx’s project. It refuses to perpetuate illusions about guaranteed historical progress or to subordinate living individuals to a future paradise.

Advanced Scientific Reflections

1) Methodological Open-Endedness

A major theme in this newly elaborated perspective is methodological open-endedness. If the “mystical shell” was never fully stripped away from Hegelian dialectics, then a truly advanced approach must keep theoretical claims provisional, subject to empirical falsification, and mindful of accidental or contingent processes in history. The author’s new viewpoint thus merges a critical reading of Marx with caution about universal laws—be they dialectical or otherwise.

2) Beyond Class Determinism

Another highlight is the move beyond class determinism: while class antagonism is a crucial engine in Marx’s analysis, it is not, by itself, the only or always the supreme factor. Modern left theories often examine gender, racial, or postcolonial oppression as separate or intersecting lines of conflict. The text calls for an integrated lens that can incorporate these complexities, ensuring that the dogmatic slogan “class explains everything” does not overshadow other relevant contradictions.

3) Freedom in the Present vs. Future Emancipation

Historically, many Marxist currents postponed freedoms “until after the revolution.” Escaping Class critiques this approach, proposing that real socialism or real emancipation must incorporate personal liberties now, not as an afterthought. This shift resonates with certain libertarian socialist or council-communist critiques, as well as intersectional feminist critiques that prioritize immediate well-being, autonomy, and self-organization.

4) Implications for Contemporary Activism

By linking theoretical discussion to activism, the author underscores that deferring freedom fosters bureaucratic or authoritarian tendencies, as evidenced by Stalinism or even Trotsky’s militaristic approach. In a more open, scientifically minded Marxism, one cannot simply rationalize oppression in the name of eventual collectivist goals. Freed from older illusions of guaranteed progress, readers or activists might explore new socio-political experiments (e.g., Zapatismo, Rojava, or other forms of local democratic confederalism) to see whether they better reconcile personal agency with structural change.

Conclusion

In Escaping Class, The scholarly contributions of Ismet Şahin have precipitated the evolution of novel theoretical frameworks and conceptualisations, thereby engendering profound shifts in the prevailing paradigms concerning numerous foundational tenets of Marx’s theoretical system. These include historical materialism, the dialectical method, class struggle, the critique of capitalism, and the epistemology of science.

- In Marx’s theoretical framework, class does not occupy an absolute primacy.

- The fundamental principle of Marxist ideology, class structure, does not serve as the primary catalyst for historical development.

- Dialectical Materialism was never a phrase Marx used explicitly, nor a single, undisputed method.

- Revolutions that neglected individual liberties in the name of class victory often ended with bureaucratic or authoritarian structures.

- The theories of Ismet Şahin, which have not been completed, are the subject of renewed interest, with the potential to create new connections between modern science, intersectionality and democratic freedoms.

- Personal Freedoms cannot be perpetually deferred without undermining the moral and theoretical foundations of any revolutionary project.

The present study sets out the position that the work of İsmet Şahin cannot simply be considered a critique of Marxism, but rather constitutes a definitive departure from the ideological tenets of the latter. The integration of a more expansive scientific perspective, the repudiation of dogma, and the insistence on the immediacy of freedom represent a dismantling of the fundamental assumptions of the Marxist paradigm.

A close examination reveals that Marxism’s reliance on historical materialism, the labour theory of value and class struggle as the primary drivers of history is no longer valid. Furthermore, the dialectical method, which assumes that contradictions inevitably result in progress, fails to account for the complexity, non-linearity and emergent nature of reality. If modern scientific insights, whether from complexity theory, quantum mechanics or systems thinking, are taken seriously, then dialectical materialism becomes a relic of a deterministic past.

However, the most fundamental break in Şahin’s thought is with Marxism’s teleology—its tendency to postpone the concept of freedom to a post-revolutionary future. This is where his intervention is most radical, as if freedom is immediate and liberation is not something to wait for but something to enact now, then the entire Marxist project collapses. The focus shifts from the mere replacement of one system with another to a state of thinking beyond systems altogether, embracing open-ended, evolving structures that reflect the real dynamics of human existence. The challenge that lies ahead is twofold: first, to articulate this fully; and second, to show not just why Marxism fails, but what stands in its place.

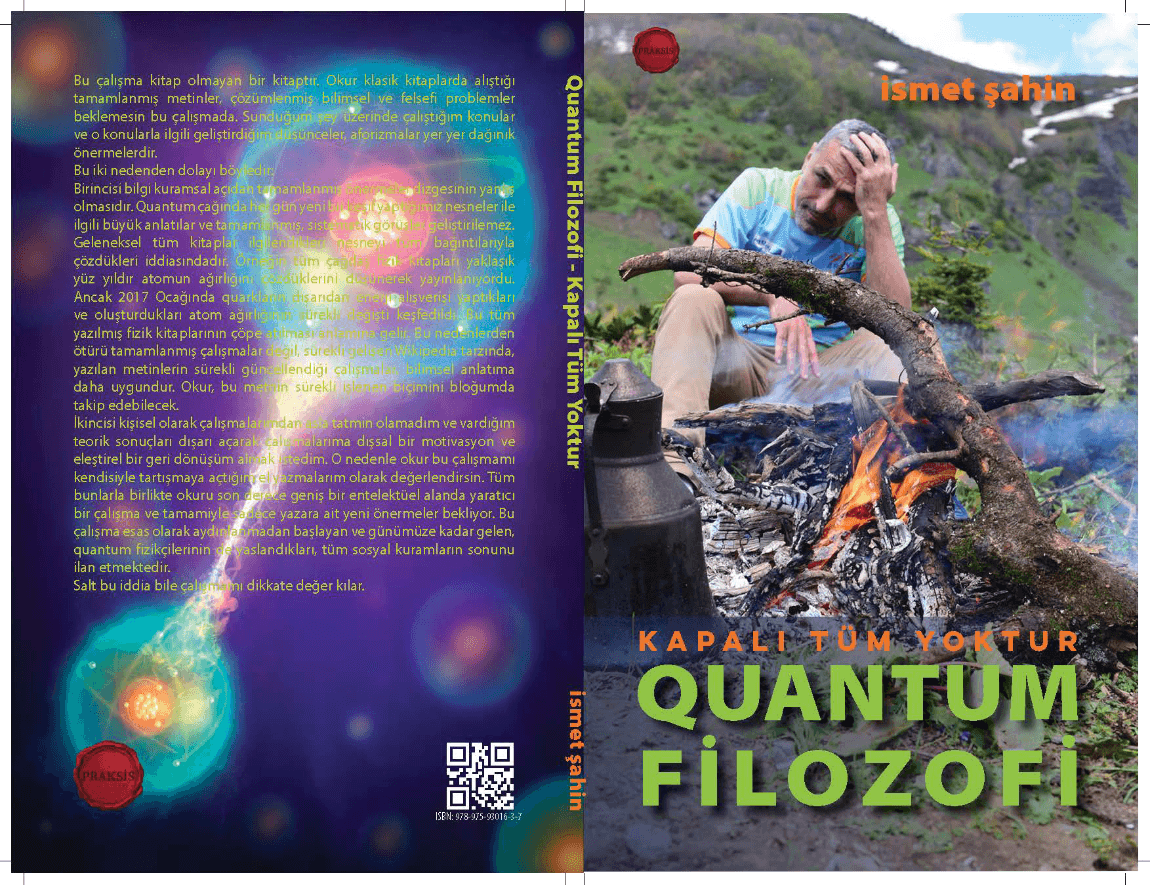

Quantum Philosophy

İsmet Şahin’s Quantum Philosophy[18] is an attempt to create a new philosophy of society, history, epistemology and science in his Quantum Mechanics studies. In this book, he confronts all metaphysical views that are influential on today’s scientific and intellectual understandings. The philosopher, who defines the Bing-Bang theory as a contemporary proof of God, also presents his thoughts against Marxism and its method, dialectical materialism, which he defines as a metaphysical understanding.

The proposition of the philosopher, “There is no closed whole”, which he developed in his book Quantum Philosophy, which will guide the theoretical studies of the future in terms of epistemology, is remarkable:

“The entire universe is an open-ended space. Closed space is a simple means of making something intelligible. The singular beginning is a reference to divine oneness. All deterministic understandings always assume a starting point of their own. Nothing arises from and evolves from a single thing. Nature, the universe, has always existed as a multiplicity, and its evolution arose as the accidental result of the intricate interactions of the many.

Let’s assume a numeric variable and construct a polynomial function dependent on it. The variable quantity will change over time and will never draw a straight line. Graphical truth is just an abstraction. The change itself is related not only to the change in quantity but also to the effect that different variables have on the direction of motion. Since it cannot be a univariate movement, its own variations will also make the movement parabolic.[18]

The human-centred view makes the studies that have been put forward with the claim of being scientific from the beginning metaphysical. The discourse claims to be philosophy, “What is the nature of this?” he asks. And then by investigating the causes of the phenomenon that it has acquired. He thinks that in this way he reveals the truth beneath the superficial phenomenon. Underneath all the arrogance of being science or scientific philosophy is this set of “discovered” reasons that are thought to be the truth.[19]

The theory of causality leaves no room for chance because it assumes that the result includes all the causes or, in more scientific terms, its variables. Deterministic viewpoints think that all variables that reveal the result that appear in history and philosophy, and of course in nature, will produce the same result under all circumstances. Some understandings, such as Marxism and positivism, which have a deterministic point of view but differ a nuance from this, see the law of nature as a synthesis of chance and causality, coincidence and necessity.

While many currents of thought and philosophers, claiming to do this, had revealed understandings and systems that they thought they had discovered reality in its entirety. Undoubtedly, these efforts have both scientific and practical benefits. But the claim that they reveal the totality, that is, everything in all its causality is a mere conjecture.[18]

Bibliography

Books

- Imperialism (editor, 2001)

- The Anti-Capitalist Manifesto (author, 2010)

- The Kid Escaped the Classroom (writer and translator, 2014)

- Quantum Philosophy (author, 2018)

Articles

- Why Are We Against Terrorism?

- On the Influence of Aristotle on Marx

- Diyalektik Platon Aristoteles Kant Hegel

- STATE-DEPENDENT RELATIONS or The State-Dependent Nature of Modern Social Movements

- Kognitif Bilissel Kapitalizm

- Hegel’s Critique of the Philosophy of History

- Philosophy’s Legacy: Understanding Its Role in Modern Science

- Frankfurt Okulu

- A PHILOSOPHER’S FICTIONALISED SEARCH FOR PARADISE

- The Marxist Theory of History

- The Rational Revolution and Hegel

- Akp Neden Gitmeli

- İmbilim Ders Notlari

- Beyefendi, Tristram Shandy’ninh hayatı Ve Görüşleri

Translations

- Bilimsel Dünya Görüşü Viyana Çevresi[20] – The Scientific Conception Of The World: The Vienna Circle[21]

- Bilim Felsefesine Kisa Bir Giriş[20] – A Brief Historical Introduction To The Philosophy Of Science, In The Blackwell Guide To The Philosophy Of Science.[22]

- Bilim Felsefesi Klasik Tartışmalar, Standart Problemler, Gelecekteki Beklentiler[20] – Philosophy Of Science: Classic Debates, Standard Problems, Future Prospects. In The Blackwell Guide To The Philosophy Of Science.[23]

References

- ↑ “İsmet Şahin (Hacettepe University) – PhilPeople”. philpeople.org. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ Jump up to:2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 ŞAHİN, İSMET (2015-01-01). SINIFTAN KAÇAN ÇOCUK (in Türkçe). Praksis Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-975-93016-2-0. Search this book on

- ↑ Jump up to:3.0 3.1 3.2 Şahin, İsmet (2010-03-28). ANTİ KAPİTALİST MANİFESTO (in Türkçe). Praksis Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-975-93016-1-3. Search this book on

- ↑ “Praksis Yay%FDnlar%FD kitapları”. www.nadirkitap.com (in Türkçe). Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ Jump up to:5.0 5.1 Gazetesi, Evrensel. “Bağımsız adaylar konuşuyor 28”. Evrensel.net (in Türkçe). Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ Şahin, İsmet. “Race Results”.

- ↑ “Bağımsızların Ortak Noktası Muhalif Olmaları – bianet”.

- ↑ “https://itra.run/Organizers/ManageEvents”.

- ↑ İsmet, Şahin. “https://itra.run/RunnerSpace/RaceResults/SAHIN.Ismet/1143731”.

- ↑ “Artvin Ultra Trail, 02 Jun, 2017 (Fri)”. Ahotu. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ↑ “Artvin Ultra Trail 2017 – Macahel Ultra Trail – 100K UTMB Index race”. utmb.world. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ↑ Artvin Ultra Trail 16, retrieved 2023-03-25

- ↑ “How Much Should We Spend on America’s Armed Forces?”. Kite & Key Media. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ Thomson, Laura (2019-05-30). “The ten most expensive military aircraft ever built”. Airforce Technology. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ “Theses on Feuerbach”. www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ https://fs.hacettepe.edu.tr/econ/photo/event/2012marx.jpg.

- ↑ “Marx, Marksizmler ve Özgürlük”.

- ↑ Jump up to:18.0 18.1 18.2 [Sahin, Ismet (2018). Quantum Filozofi. Ankara, Turkey: Praksis. ISBN 978-975-93016-3-7 “Quantum Filozofi”]. scholar.google.com.tr. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ Şahin, İsmet. “https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323153490_QUANTUM_FILOZOFI_-_KAPALI_TUM_YOKTUR”.

- ↑ Jump up to:20.0 20.1 20.2 ŞAHİN, İSMET (2015-01-01). SINIFTAN KAÇAN ÇOCUK (in Türkçe). Praksis Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-975-93016-2-0. Search this book on

- ↑ Uebel, Thomas (2020), “Intentionality in the Vienna Circle”, Franz Brentano and Austrian Philosophy, Vienna Circle Institute Yearbook, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 24, pp. 135–168, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40947-0_7, ISBN 978-3-030-40946-3, retrieved 2023-03-25

- ↑ Machamer, Peter (2008-01-21), Machamer, Peter; Silberstein, Michael, eds., “A Brief Historical Introduction to the Philosophy of Science”, The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Science, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, pp. 1–17, doi:10.1002/9780470756614.ch1, ISBN 978-0-470-75661-4, retrieved 2023-03-25

- ↑ Worrall, John (2008-01-21), Machamer, Peter; Silberstein, Michael, eds., “Philosophy of Science: Classic Debates, Standard Problems, Future Prospects”, The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Science, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, pp. 18–36, doi:10.1002/9780470756614.ch2, ISBN 978-0-470-75661-4, retrieved 2023-03-25

External and Internal Links

- Karl Marx: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Marx

- Friedrich Engels: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Engels

- Dialectical Materialism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialectical_materialism

- Das Kapital: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Das_Kapital

- October Revolution: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/October_Revolution

- Stalinism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalinism

- Trotskyism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trotskyism

- Western Marxism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_Marxism

- Frankfurt School: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankfurt_School

- Paris Commune: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Commune

- Internal passport (Soviet Union): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internal_passport_of_the_Soviet_Union

- Gulag: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulag

- Vladimir Lenin: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Lenin

- Georg Lukács: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Luk%C3%A1cs

- Antonio Gramsci: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Gramsci

- Theodor W. Adorno: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_W._Adorno

- Herbert Marcuse: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Marcuse

- Chronology of Social Science: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/19th_century_in_social_science

- Plato’s Republic: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plato%27s_Republic

- Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicomachean_Ethics

- Letter to Joseph Weydemeyer: https://marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/letters/52_03_05.htm

Footnotes: Toward a New Theory of Science

- The context of the “Marx, Marxisms and Freedom” conference.

- Engels’s expansions on dialectics (e.g., Anti-Dühring) as potentially universalizing or metaphysical.

- Marx’s references to classical economics in Capital (volume 1, p. 20) and the more detailed notes in Theories of Surplus Value.

- Marx’s discussions of Ricardo’s abstractions in Theories of Surplus Value, p. 451.

- R. Rosdolsky’s The Making of Marx’s “Capital” for advanced textual analysis.

- Letters by Marx referencing class conflict preceding him.

- Plato’s Republic (415 a–b–c) and Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (1094a) as ancient references to classification.

- Historical expansions on forced labor in the Soviet era, referencing official GPU accounts, and expansions to millions of prisoners.

- Lenin’s speech (Collected Works, vol. 24, p. 24, Third Congress of Soviets) regarding the necessity of the German revolution.

- Engels’s caution from The Peasant War in Germany about the pitfalls of taking power prematurely.

Review

92%

Summary This site is dedicated to the philosophy of Ismet Şahin, emphasizing the concept of open-ended thought. It invites exploration of his ideas on breaking away from fixed perspectives, fostering continuous inquiry, and embracing the complexities of knowledge and existence. Through essays, discussions, and resources, visitors are encouraged to engage with the infinite possibilities of thought and to challenge conventional boundaries in philosophy.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks