STATE-DEPENDENT RELATIONS: The State-Dependent Nature of Modern Social Movements

State-Dependent Relations in Historical Context

Human-Dependent vs. Commodity-Dependent Relations

Marx, in line with the theoretical conclusions he reached in his studies on political economy, divides social relations into two categories: human-dependent and commodity-dependent relations. Human-dependent relations refer to the relationships that individuals and society are forced to establish for the reproduction of their biological and species existence. This historical moment is driven by the process of human production and the use-value produced by human activity, compelling people to interact with one another1.

The Transition from Use-Value to Exchange-Value

Commodity-dependent relations, on the other hand, refer to the capitalist era, which Marx defines as the time when social and individual actions are subject to the production, circulation, and accumulation of commodities. In this sense, Marx’s theory of alienation critiques capitalism as the process through which humans lose their essential human qualities2. Communism, for Marx, represents humanity’s liberation from commodity-dependent relations, or what he calls the fetishism of commodities3, and all forms of alienation. It envisions the establishment of genuinely free human social relations, in which individuals participate of their free will4.

Critiques of Marx’s Anthropomorphic Assumptions

Marx makes two significant errors. First, he assumes that in history there was a given human, unaffected by commodities, and therefore unalienated, resembling a Christian figure before committing the original sin and being expelled from paradise5. This assumption is an anthropomorphic approach that has influenced social sciences through religious ideologies and also impacted Marx6. Therefore, Marx’s theory of alienation can be seen as a materialist continuation of Christian theology, as filtered through Feuerbach7. In this sense, Marx’s theory of communism follows the tradition of classical utopian thinkers8.

Contrary to the anthropomorphic perspectives of Marx and others, there is no pre-existing, assumed human, no ideal communal society that has since been lost, nor any essential human nature that was later alienated9. A society that does not produce surplus products, or one that remains tied solely to the production of use-values, cannot generate history10.

The glorification of such societal forms only sustains the primitive human condition. This can be easily observed in the differences between the indigenous peoples of South and Central America (like the Aztecs and the Mayans) and the indigenous peoples of North America. While the South American civilizations advanced to the point of independently developing their own writing systems, the North American indigenous peoples retained their “human essence” for thirty thousand years, remaining unalienated11.

Redefining Alienation and Surplus Production

The Role of Surplus Production in Humanization

Alienation is defined as the social relations that evolve with the production of surplus products—namely, the excess value produced and consequently the appropriation of that surplus12. The state, as it develops alongside these relations, is also considered in a negative context. Thus, from a class perspective, the emergence of the state is defined as a coercive mechanism for the ruling class to produce and sustain surplus production and to appropriate it13. However, states did not initially arise as mechanisms of class oppression created by the division of labour.

They gained this function over time but originally emerged from the genuine struggles of primitive societies against one another and against nature14. State forms developed even without clear class distinctions or as significant variables in social life15. These structures were formed not only as tools to preserve biological and species existence but also as instruments for maintaining religious life16. New anthropological findings have shown that humans built sacred sites and temples, and organized complex systems within these religious structures, before transitioning to settled life17.

The second clear error becomes evident within this framework: the negative view attached to surplus production and the state18. Surplus production is not the cause of human alienation or, as if there were some “human essence,” the loss of that essence. On the contrary, surplus production forms the real material basis of humanization19.

The humanization of humans began when they developed tools and culture for the production and maintenance of surplus, transitioning away from spending all their time, like animals, on meeting their biological needs. Human liberation, therefore, is not about glorifying sacred labour in the Catholic sense, but about achieving freedom from work and increasing the time available for self-development20.

When Aristotle heard from a philosopher returning from Egypt that the Egyptian priests had made incredible advancements in all areas of science, he responded, “It seems they have a lot of free time”21. From this perspective, if we consider history in its entirety—especially considering humanity’s given level of development—states emerge as the tools of humanization, of the production, development, preservation, and reproduction of social structures and cultures22. The negative critiques of states, as seen in Marxism and other theories, stem from the fact that these critiques abstract and isolate the state as merely an instrument of class oppression23.

State Critiques and the Path to Reform

States are not just instruments of destruction; they are also real tools for the production, preservation, and reproduction of humanity’s social and cultural-scientific existence24. What we need to eliminate are the negative functions of states, not the states themselves25.

Towards a Complex Historical Science

History as an Infinite Matrix of Variables

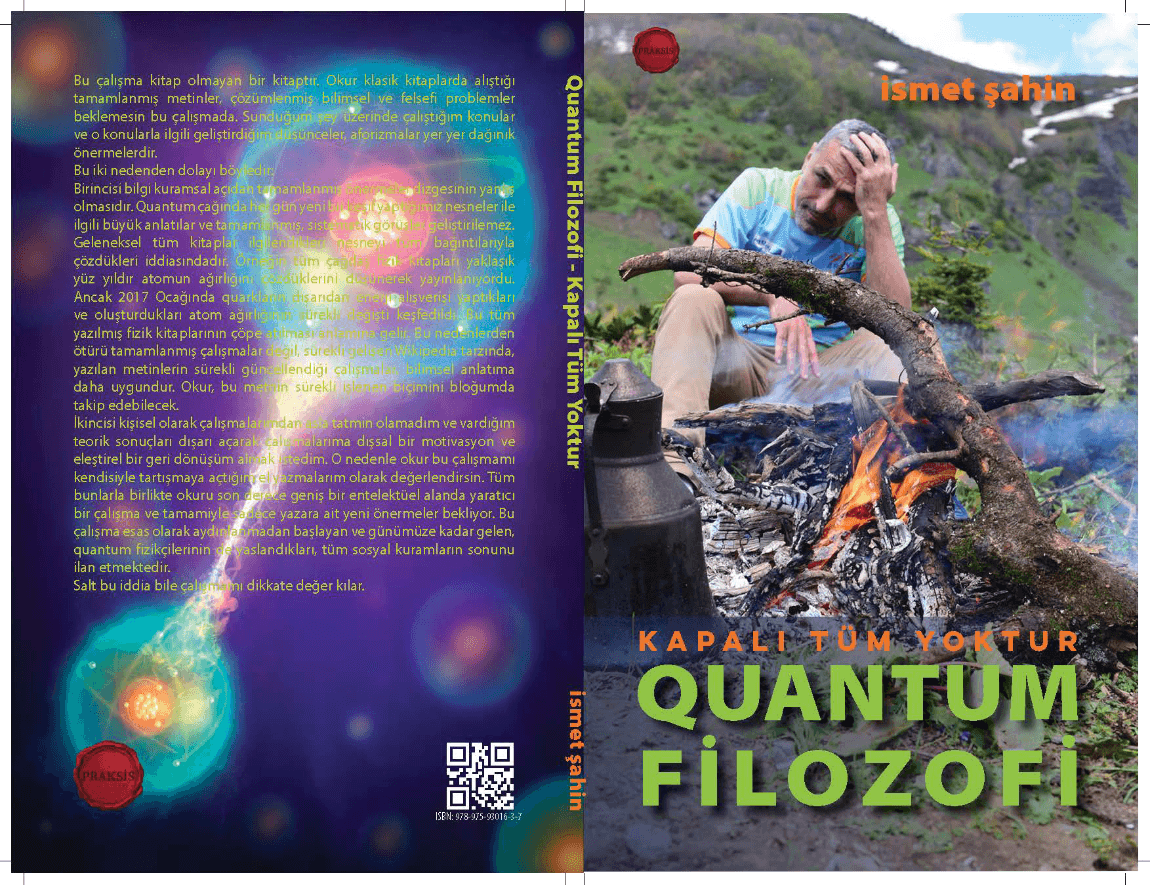

Therefore, it can be said that history cannot be reduced merely to the human and commodity-dependent relations described by Marx26. Marx sought to understand the laws governing society’s reproduction and the real foundations of social relations27. As a political economist, he made an economic reduction28. In addition to human- and commodity-dependent relations, I also introduce the concept of state-dependent relations29.

By state-dependent relations, I mean that states are fundamental components of the processes of social reproduction and are the primary variables of the function called history30. Thus, history cannot be reduced to the struggles of two classes or two variables31. History is the product of an infinite matrix of variables32. As we discover these variables, we begin to produce historical science33.

Introducing State-Dependent Relations

No social-historical or natural movement can be reduced to just two or three variables34. Limiting the variables in any movement is a method used to make complex phenomena understandable35. In reality, every movement consists of infinite variables, and the task of science is to discover these variables36.

History is the product of the intertwined and composite effects of infinite variables, both in nature and in human society, arising from the movements of individuals and their activities37. History did not emerge through human will or as a result of social relations that individuals deliberately engaged in38. This view reflects the theological and teleological perspectives that place humans at the center of world history, a perspective that has influenced social theories, including Marxism39.

Footnotes

- Marx, Karl. Capital, Vol. I. Penguin Classics, 1976, p. 163. ↩

- Marx, Karl. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. International Publishers, 1964, p. 71. ↩

- Ibid., p. 165. ↩

- Ibid., p. 171. ↩

- Marx, Karl, and Engels, Friedrich. The German Ideology. International Publishers, 1970, p. 47. ↩

- Feuerbach, Ludwig. The Essence of Christianity. Harper & Row, 1957. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Engels, Friedrich. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Progress Publishers, 1970, p. 36. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p. 199. ↩

- Wolf, Eric. Europe and the People Without History. University of California Press, 1982. ↩

- Engels, Friedrich. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Penguin Classics, 1972, p. 202. ↩

- Ibid., p. 208. ↩

- Ibid., p. 212. ↩

- Ibid., p. 218. ↩

- Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harper, 2015, p. 150. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Marx, Karl. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, p. 84. ↩

- Engels, Friedrich. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, p. 212. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- de Grazia, Sebastian. Of Time, Work, and Leisure. New York, 1962, p. 34. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society, Vol. I. University of California Press, 1978, p. 56. ↩

- Lenin, Vladimir. The State and Revolution. Penguin Classics, 1993, p. 43. ↩

- Engels, Friedrich. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, p. 220. ↩

- Marx, Karl. The German Ideology, p. 56. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Marx, Karl. Capital, Vol. I, p. 161. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society, Vol. I, p. 60. ↩

- Engels, Friedrich. Dialectics of Nature. Progress Publishers, 1954, p. 78. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Engels, Friedrich. Dialectics of Nature, p. 83. ↩

- Marx, Karl, and Engels, Friedrich. The Communist Manifesto. Penguin Classics, 2002, p. 54. ↩

- Ibid., p. 92. ↩

- Ibid., p. 95. ↩

- Ibid., p. 96. ↩

- Ibid., p. 100. ↩

- Engels, Friedrich. Dialectics of Nature, p. 101. ↩

Review

84%

Summary This paper, authored by philosopher İsmail Şahin, explores the concept of state-dependent relations, expanding on Marx’s theories of human- and commodity-dependent relations. It critiques the limitations of Marx’s views on alienation and surplus production, emphasizing that surplus production is integral to humanization rather than alienation. Şahin introduces the idea that modern social movements are not independent but functions of state control, influenced by global and local state struggles. Through case studies like the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Arab Spring, and the Gezi Park protests, the paper demonstrates how modern social movements operate within the gravitational pull of states, where states play a central role in shaping societal reproduction processes and the trajectory of revolutions.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks