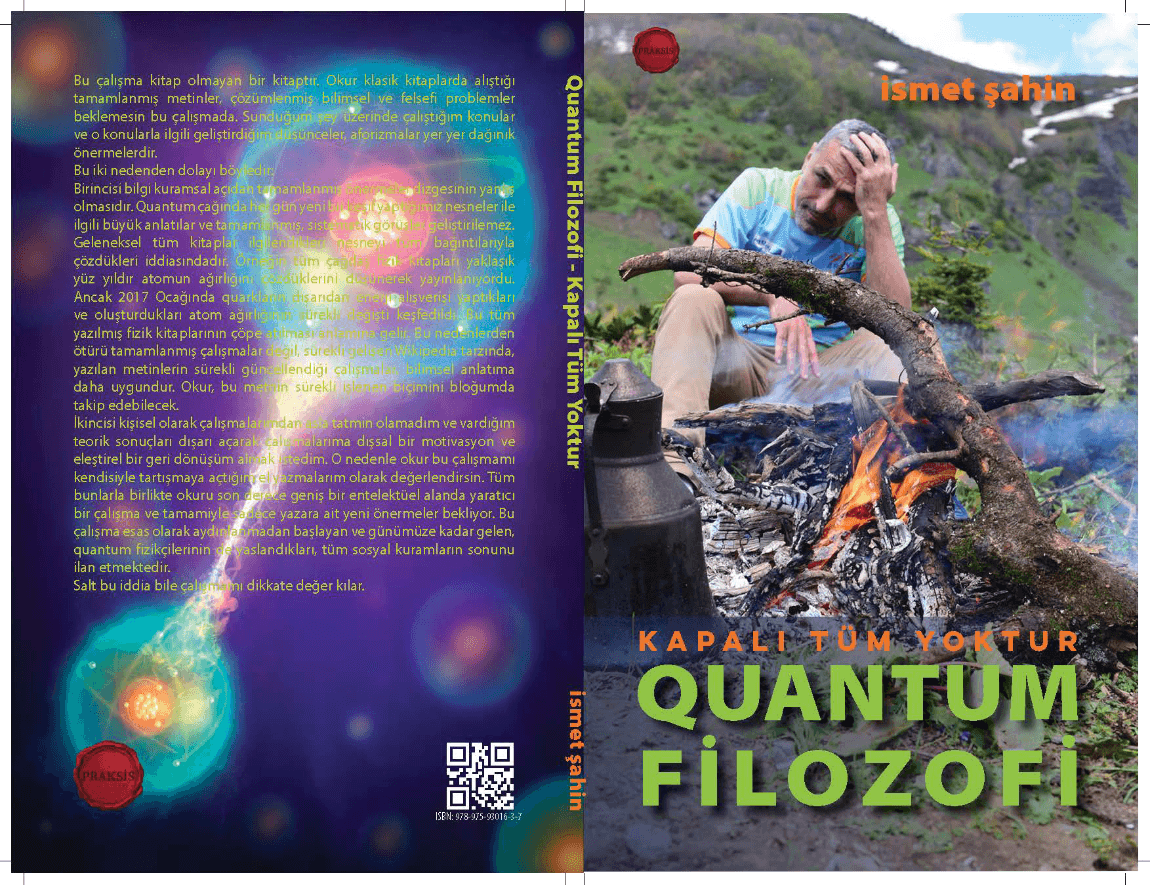

On the Influence of Aristotle on Marx

To the uninitiated, the connection between Marx’s theoretical framework and the ideas of a philosopher from the democratic era of Ancient Greece may appear incongruous. Marx was influenced not only by Aristotle but also by the entire corpus of philosophers from Ancient Greece. He frequently drew upon the works of Heraclitus, Democritus, Epicurus, Plato, and other philosophers as sources for his books.

The present study will focus on the relationship between Marx and Aristotle. The impact of Aristotle on Marx is evident. The prevailing view among contemporary scholars is that the influence of Aristotle on Marx was primarily mediated through Hegel. While this mediated influence is evident, it is nevertheless partial. Despite the fact that the modern Western philosophical tradition, including Descartes, derived its empirical foundations from the developing natural sciences, it is clear that its main theoretical inspiration came from Ancient Greece. The formation of the modern Western philosophical tradition is characterised by a direct influence and even an exaggerated transference of Ancient Greek thought. In light of the contemporary tendency to draw upon the intellectual legacy of Ancient Greece for scientific pursuits, it is perhaps unsurprising that during the early stages of the scientific revolution, thinkers would turn to the ancient Greek tradition, and in particular to Aristotle, the most influential philosopher in history. Aristotle is the philosopher in the history of philosophy who has left the most comprehensive impact on the development of philosophical thought. Marx is one of the thinkers who was profoundly influenced by Aristotle’s intellectual legacy. The socio-economic roots of influence are evident in the establishment of democracy and the development of intellectual wealth in Ancient Greece. These were based on the free trade in commodities, which flourished from Iran to the Middle East and from Egypt to the Black Sea. In the hinterland of these commercial relations, a sophisticated intellectual interaction and its products emerged. From the outset, upon the arrival of the ancient Greeks in their new homeland, they began to utilise their own alphabet, derived from the Phoenician script.

Aristotle’s theoretical influence is derived from his status as the final heir and representative of the centuries-old cultural tradition of ancient Greek thought. The depth of abstraction that would later develop only under capitalism reached its zenith with the Greek commercial life itself and subsequently collapsed. Aristotle, nourished by this theoretical maturity, developed profound views on several key concepts, including abstract labour, taxonomy, logical categories, laws of motion, logic, ontology, dialectics, and almost every field that would influence all future generations. All thinkers seeking answers to their contemporary problems in medieval Europe, where commercial life began to flourish once more, therefore found in ancient Greece theoretical refuges in which they could safely take refuge.

On Economic Theory

The economy is a commercial relationship between individuals and is therefore intrinsically linked to all legal, political, social, and moral spheres. In the initial volume of Capital, Marx posited that, under specific historical circumstances, the economy is a relationship between individuals. However, these relations could only be observed as relations between the products of human production and the consumption of those products. Moral economics, therefore, not only elucidates the nature of the economy but also illuminates the lived experiences of individuals and their responses to these circumstances. Aristotle devoted considerable attention to the moral implications of economics. His primary concern was not production efficiency; rather, he emphasised the effects of production on the good life, freedom, and community. Even a cursory comparison reveals that Marx, like Aristotle, derives ethical considerations from the concept of production. Aristotle restricts the scope of production to technical (technological, artistic) considerations.

Marx, in a manner similar to that of Aristotle, establishes a connection between significant economic structures, including the accumulation of wealth, and the social division of labour. Hegel shares this perspective. Aristotle posits that production and action are distinct entities, with no inherent relationship between the two. He asserts that action is not a form of production, and production is not a form of action. In his writings, he states: The technical cause, which is the cause of the realisation of production, and the ethical cause, which is the cause of the realisation of action, are two completely distinct phenomena. Marx concurred with Aristotle on this matter, stating that “production is determined by technical causes.” Additionally, Marx’s theory of communism was influenced by Aristotle’s model of the household economy, which served as a foundation for the conceptualisation of a new household economy. Marx’s theory of labour makes a direct reference to Aristotle’s concept of happiness. In Marx’s theory, human activity is defined as the direct endeavour to satisfy one’s own needs. This is, of course, the personal benefit from which Marx derives the concept of use value. Marx acknowledges the validity of some of Aristotle’s perspectives. The most significant of these is Aristotle’s identification of the distinction between use value and exchange value, as discussed in the preceding paragraph. In a seminal work published centuries before his followers, Aristotle elucidated the genesis of money from the value form of commodities. He explicitly stated that the common property of two distinct physical commodities is contained in a third commodity. Some scholars, such as Gilbert, have proposed that Aristotle exhibited a greater degree of sophistication in this regard than Marx and the classical economists at the level of abstraction. This interpretation is undoubtedly exaggerated, but given the age of Aristotle and the level of commodity circulation at the time, it is not without merit. Marx wrote in Capital that ‘In the first place, Aristotle quite clearly meant the money form of the commodity as merely a more developed form of the simple form of value.’ He gives the example of expressing the value of one commodity in terms of another by means of randomly selected commodities.

The notion that five beds equate to one house is no more distinguishable than the idea that five beds represent a specific monetary value.

In his analysis, Marx asserts that Aristotle identifies two fundamental categories of value: qualitative and quantitative. Marx, like Aristotle, conceptualises freedom as the absence of compulsory labour, or the absence of labour spent for necessary needs. In his Metaphysics, Aristotle posits that the Egyptian priests had sufficient leisure time to engage in contemplation. In the view of Aristotle, scientific productivity and freedom represent an expansion of leisure time in relation to the time spent on compulsory labour. Marx’s concept of freedom is consistent with that of Aristotle in that it is entirely free from compulsory labour, that is to say, from the labour – work – that people are obliged to perform in order to survive. He associates this with the level of development of the productive forces. Marx’s theory of alienation appears to have been influenced by Aristotle’s understanding of nature. Marx advances the argument that Aristotle’s concept of natural justice is applicable to the context of wage labour, which he characterises as unnatural. The second law of the dialectic of Hegel and of Marx’s dialectic, which is derived from the former, is taken entirely from Aristotle. This law pertains to the transformation of quantity into quality and vice versa.

Marx unifies Aristotle’s differentiations between praxis, theoria, and art under the overarching concept of praxis. He takes praxis to be conscious of human activity in itself. In point of fact, this is a tautology. As Aristotle asserts, all human activities are conscious insofar as they are zoon politik. It is a fallacy to suggest that human activity can be unconscious. In his work, Aristotle classifies activities according to their subjects. Each corresponds to a way of life. The concept of material cause, as developed by Aristotle, forms the basis of philosophical materialism, as introduced by Feuerbach. The theory of knowledge proposed by Aristotle is characterised by an inductive and deductive dual structure. In the former, conceptual generalisations are reached, while in the latter, inferences are made from the universals reached by moving from concept to concept. Marx employs this method with a Hegelian distortion.

One Last Note

If we consider Aristotle’s system as a paradigm extending from philosophy to economics, politics, logic and the philosophy of science, it is challenging to assert that contemporary theories have surpassed this paradigm. Qualitative and quantitative accumulations remain within the same paradigm.

The depth of Aristotle’s thought is best understood in the context of the intellectual traditions of Ancient Greece, which were shaped by a distinctive form of free rationality. Marx famously described Ancient Greece as representing the “pure, aesthetic beauty of the childhood of humanity,” a period that humanity has long since left behind. To overcome this legacy, any subsequent developments in thought must take into account the unique characteristics of the ancient Greek intellectual tradition.

Review

98%

Summary The essay on the influence of Aristotle on Marx offers an insightful exploration of the philosophical connections between these two significant figures. It presents a compelling argument for Aristotle's impact on Marx's theoretical framework, emphasizing how Ancient Greek thought laid the groundwork for modern philosophical discourse.The introduction effectively sets the stage by addressing the surprising connection between Marx and a philosopher from ancient Greece, drawing the reader in. The detailed examination of economic theory, particularly the distinctions between use value and exchange value, provides a nuanced understanding of how Aristotle's ideas resonate within Marx's work. The essay successfully highlights the moral implications of economics, linking them back to both philosophers' concerns about the good life and community.Overall, the essay is well-researched and thoughtfully structured, providing a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between Aristotle's and Marx's ideas. It captures the depth of Aristotle's influence and situates it within a broader historical and intellectual context. The concluding remarks could benefit from a stronger summarization of key points and their contemporary relevance, but the essay overall presents a rich and engaging discussion that invites further contemplation on the ongoing significance of these philosophical legacies.