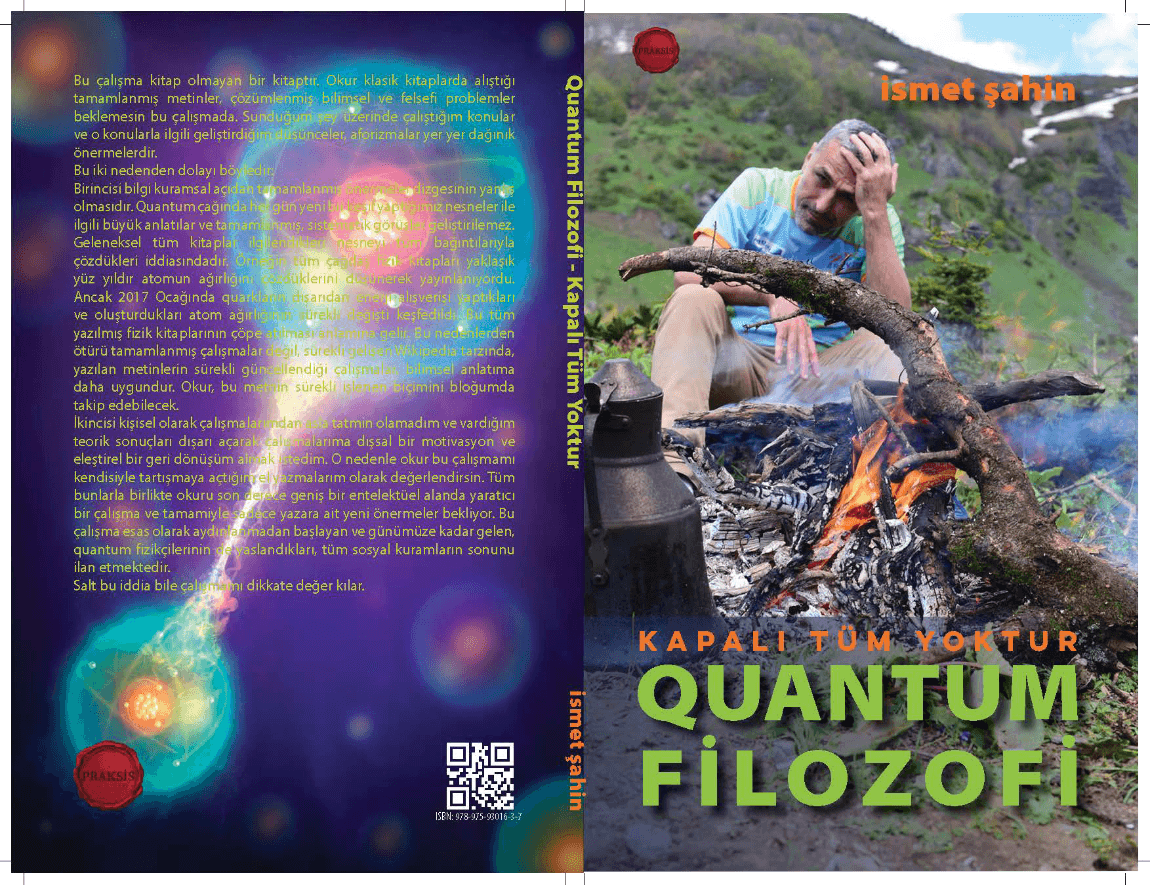

A PHILOSOPHER’S FICTIONALISED SEARCH FOR PARADISE

A PHILOSOPHER’S FICTIONALISED SEARCH FOR PARADISE

The Critique Subject: Essentially, Constructive (Hegelian Philosophy) is Not Philosophy. We will primarily focus on Hegel’s introduction to his science of logic and Aziz Yardımlı’s introduction and his own stance.

The Historical Adventure of Philosophy

In our age, the development of sciences has influenced philosophy, revealing a general tendency towards empirical data, sensation, and experience in philosophy as well. This inclination mainly stems from the desire and effort for philosophy to provide certainty at least as much as positive sciences do. Hegel’s philosophical system collapsed under Feuerbach’s materialistic criticisms, leading philosophers to new searches. This search was first manifested in a return to Kant. However, Kant’s philosophical system was subjected to an empirical distortion to align with the dominant spirit of the era. Secondly, Comte’s Positivism, although proposed as a social theory, has had a lasting effect on philosophy. New positivism, Positivist Logic, Pragmatism, Analytic, Structuralism, Linguistic, and various other philosophical movements emerged and were proposed under this influence. Even though Neo-Platonic and Neo-Idealist movements (like A. Yardımlı) were formed in reaction to the first ones, they could not significantly impact the contemporary era. An exception is Husserl’s Phenomenology, which had a certain level of influence—e.g., Hartmann (Critical Ontology), Breton (Surrealism), Heidegger (Existentialism)—but this too quickly faded after a brief flourish against the prevailing positivist trend.

Positivism considers empirical data as the object of knowledge. Empirical “fanaticism” possesses a lack of thought to which we will raise many objections; however, our approach to philosophy is entirely different from A. Yardımlı’s: “Where the conceptual constructs end, that is, in real life, science begins, namely, the practical processes of human activities. The empty talk about consciousness ends, and real knowledge replaces these verbal discussions. Where reality is unveiled, philosophy loses its environment of existence as an independent field of knowledge… The issue is to explain these theoretical remarks based on existing conditions. The elimination of these remarks is not achieved by theoretical studies but by the changed conditions.” — The German Ideology, K. Marx.

Aziz Yardımlı critiques the empirical tendency in philosophy, stating, “Philosophy education today serves as a tool for examining its own history rather than the Truth. The logical construct of the 20th century has firmly embedded itself in a philosophy consciousness that has lost the ability to track, and the unifying power of the intellect has yet to reveal itself in the modern interpretation of the history of philosophy. Philosophy has been distorted by a foreign empirical fanaticism, and philosophical passion itself has dulled.”

Almost everyone, including all “empirical fanatics,” agrees with A.Y.’s first sentence. It is a fact that every philosophical trend laments the current state of philosophy. But equally, the positivist movements argue that it is not philosophy but constructive philosophy that has exhausted its utility. Undoubtedly, while positivists exhibit historical consciousness deficiencies in this assertion, they have strong bases derived from contemporary life.

Thought and Reality of A. Yardımlı

At Yardımlı’s request, let us briefly return to ‘reality.’ And let’s begin with Hegel.

“Philosophy is undoubtedly good for its objects in common with religion. Both take reality as their objects and moreover, in the highest sense, in the sense that God is reality and only He is reality” (Science of Logic, p. 1).

Hegel’s system also calls us to seek reality but on the condition of accepting God as the unique reality. This reality is first revealed as the idea of itself in Logic (God). Then Spirit externalizes itself. Spirit wants to create its otherness. Here, God, being compressed in Himself, decides to play and creates the universe, the world, and time, thus becoming Nature—the Spirit manifesting as Nature. Ultimately, by realizing its history and consciousness within man, it understands that this entire historical adventure is a game it plays for itself, achieving its own consciousness. Until the next game of God, this game has ended. At least as far as life and thoughts about life continue, Hegel declares it so. Is Yardımlı calling us to a reality that means God is reality?

Yardımlı knows that this is a naive attitude and constitutes the weakest point of Hegel’s philosophy. Moreover, this is the most dominant aspect of the empirical critics of Hegel. Therefore, Yardımlı’s first task will be to free himself from Hegel’s weak point. “Despite all the theological tendencies that constructive philosophy undertakes in Hegel and other European philosophers, it is indeed the only possible dimension of truly free scientific thought, and the distinction between philosophy and religious consciousness is of the same kind as the distinction between philosophy and everyday consciousness and empirical sciences.” – Aziz Yardımlı.

In fact, Yardımlı should not have debated this on this ground; at least, he could have completely rejected Hegel’s reduction of philosophy to theology. This would have been more consistent for him. The understanding of religion or divine consciousness in human daily life is given. It does not require special consideration, as historically, human religious consciousness developed before philosophical consciousness. More precisely, throughout the history of philosophy, religious understanding has always been prior to philosophy. Here, Yardımlı is doing what Hegel did not do and frankly failing: accepting empirical sciences as being at the same distance from philosophy and religious consciousness, failing to see the historical development and sequential order of these.

Empirical sciences each have their own specific objects. The object of physics is matter, while that of chemistry is molecules, sociology is society, etc. What is the object of religious consciousness? God! What is the object of philosophical consciousness? God! (Of course, according to Hegel.) Hegel states with clarity that philosophy’s object is indeed intertwined with religion. The direction of philosophical consciousness is with thought, while religion is with intuition and belief, relating to the method of attitude and orientation towards the external world of consciousness.

Yardımlı proposes a Constructive Philosophy freed from “theological” tendencies. But this means he is confronted with another problem. He must explain what the truth we need is if it is not God. Thus, he will clarify one of the problems that form the focus of philosophical discussions in our time – What is the object of philosophy? However, throughout the entire 77 pages he wrote in book form, he vainly asserts that only when we approach the Truth with constructive thought can we save philosophy from its “empirical banality.” However, even a superficial look at the history of philosophy will show us that the theological tendencies in philosophy stem from philosophy’s constructive form.

There cannot be a Constructive Philosophy without theology or every Constructive Philosophy ultimately leads to God and theology, as with Hegel. If Yardımlı removes the truth from being God and gives it content independent of God and, of course, subjective spirit, he must also give up calling us to constructive philosophy. He cannot abandon this, because then he must take the truth as matter, which in turn means he cannot propose constructive philosophy to us.

What is the Constructive Philosophy to which Yardımlı calls us? Constructive philosophy is the term Hegel used to characterize his own philosophy. According to Hegel, a logical doctrine has three aspects: the abstract (conceptual reason) aspect, the dialectical (negative reason) aspect, and the constructive (positive reason) aspect. Hegel accused the philosophies before him of being abstract, one-sided, that is, metaphysical. He thought his own philosophy transcended all other philosophies by encompassing them.

His philosophy is merely a play of concepts. It is formed with concepts and is disconnected from practice as the system of the determinations of the concept. It has been produced through purely fictional (speculative) intellectual effort that does not start from scientific data. “Here, it is clear that we need to distance ourselves from both the indifferent empiricism that reduces the established cultural structure to an insignificant appendage and the rationality of Europe’s Theological mindset, and to return to that constructive spirit that began much earlier on the shores of Lyon and created philosophy as the free science of reason.” – A. Yardımlı.

What is clear is that Yardımlı carries and conveys a longing similar to that of a ‘philosopher’ who cannot understand the historical evolutionary direction of human thought but is not satisfied with the emerging form, expressing a longing akin to that of enslaved people experiencing shock and fear over what has happened to them, as they express their yearning for their former communal lives. Those people never fulfilled their longings. As a result, they idealized their past: hoping to reunite someday in the future, some told their children it would be in the Sun State and others in the Golden State. Finally, they transformed their longings into a heaven they would reach after dying in the afterlife, never to be attained during their lifetime. Yardımlı is not saving philosophy from the situation he has fallen into, nor can he. In front of a child asking what the state of philosophy is, he is embarrassed. He cannot suggest a future for philosophy; rather, he advises the child to look for the future of philosophy in its past.

However, Reason has, at least since the 17th century, with the development of natural sciences, reached a position where it can stand on its own feet, contrary to Yardımlı’s assertion. In this form, Reason is not whimsically blowing into the depths of space; it is science that prevents it from imposing the external (Metaphysics) on us as rational. Moreover, ‘damned’ this science is empirical.

Here, let’s open a parenthesis: We must not confuse the ‘empirical concept’ we use with philosophical empiricism. From the perspective of Marxist epistemology, empirical data is the first stage of knowledge, while theoretical effort is the second stage. Empiricism, however, asserts that the only sources of knowledge are empirical experiences. In this respect, if we were to use Hegel’s language, it would be a ‘simple understanding view’ that separates and confronts these two stages of knowledge acquisition by reason. Undoubtedly, Yardımlı falls into the same mistake from the perspective of the constructive mood.

Following this, Yardımlı wants philosophy to escape from this ‘empirical’ captivity and return to the Paradise where Reason can freely fly, to the constructive spirit.

However, just as the end of philosophy has come, showing the emotional reaction of people who have lost their ‘paradises’ to “nonsensical views,” he weakens the foundations of his claims by stating that “philosophy has never been understood, recognized, or esteemed in its genuine real sense in Europe.” If only he had at least investigated the reality of these claims instead of making a serious assertion, he would have undoubtedly done a much more useful job in the name of philosophy.

Yardımlı’s criticism leads to outcomes; indeed, many ‘newly’ labeled movements have emerged that derive from the belief that philosophy has come to an end but leads their investigations to unscientific conclusions. However, what Yardımlı overlooks is that, while reacting against empiricists, he proposes a new Hegelianism abstracted from the theological side, standing on the same ground as them. What he suggests is that we seek the paradise of constructive philosophy for the resurrection of philosophy: But Paradise is not here; it is in the other world.

THE DEPTH OF THE PHILOSOPHER

In this section, we will see how Yardımlı criticizes other authors and movements. “In reality, the motives of these kinds of writers are often various subjective impulses such as jealousy (Schopenhauer), career (Russell), livelihood, personal issues, or political pretensions (Marx), etc., and none of them show even the slightest trace of the spirit of free thinking.” The depth of Yardımlı’s criticism of the actions of historical figures and political or thought traditions astonishes us. Each of the thought structures and individuals has its own separate critical levels in different styles and forms. Mixing these levels is, especially in our time, the greatest confusion that the Frankfurt School and post-Marxists have fallen into. The confusion manifests itself when, for example, examining or criticizing a social phenomenon while operating with the concepts and methods of psychology. Yardımlı is also caught in this fallacy we call psychologism. “… the motives of the authors… can be various subjective impulses.”

With this explanation, Yardımlı is initially trying to convey the message: These writers have written their thoughts under the bondage of subjective impulses. That is, they are not objective and scientific. Therefore, it does not require extensive discussion. Therefore, you will appreciate that I have also saved myself and you from great efforts by finishing their work in such a sentence.

While contemporary psychology considers human thought and behaviour as conscious (rational) activity, Yardımlı’s reduction of human thought and, moreover, the theoretical level of this thought to the emotional reactions of people shows how little he understands psychology. In human intellectual or practical activity, there is, of course, a share of both social conditions and subjective impulses. However, even subjective impulses make themselves indirect as thought acts in the mental process.

Undoubtedly, if thought is to be criticized, one should look at the internal consistency and suitability of the criticized thought, but not at the subjective positions of the thinkers, as this is completely unrealistic. If one wants to take up and criticize a thought in this framework: 1 – The logical consistency of the thought. 2 – Its suitability to its object. 3 – The material conditions and contexts of the time in which 1 and 2 were formed as their historical background must be examined.

This means that Yardımlı does not do these, nor does he essentially ‘criticize’ these thinkers based on subjective impulses but rather screams the panic of a ‘philosopher’ who has been confronted with the reality of the greatness of these thought structures.

A. YARDIMLI DEEPENS MARXISM

Let’s come to the scream Yardımlı lets out in the face of Marx. In his words, “Marx was not the first to ask whether it is possible to realize free thought in the historical process. He was just the one who turned the past into a new system.” Yardımlı wants to turn the gaze of his readers toward one of the commonalities of Marxist thinkers and movements – a unified ideological criticism of capitalism. But this is the most illogical position. This means that Yardımlı is not going to deepen Marxism but rather contradict it by passing through a completely idealistic tunnel.

Marxist epistemology asserts that thought and being are related to each other through the historical development of material conditions. The material conditions form the context of thought, thus giving a specific content to thought. No thought can escape from its historical and material conditions and be considered free thought. This is not only true for Marxism but also applies to the totality of human thought. Here, Yardımlı does not understand that the objection of contemporary ‘empirical’ trends is not to the material conditions, but rather to the historical understanding of thought. Thus, Yardımlı remains oblivious to the reality of Marxism.

He overlooks the failure of Marxism and how Marxists should now confront this failure. Instead, he reflects on Marxist discourse with a contemporary ‘theological’ fear. He positions his readers to look for a new “constructive philosophy” and tries to embed a disorganized vision of thought behind it.

In one of his letters to Engels regarding Capital, Marx laments, “There is no other writer in history who has written about money and struggled with it as much as I have.” Marx could have easily lived as a rich bourgeois professor, flattery to his wife’s wealthy and noble family as many do, and as is currently done, in fame and wealth. However, he never betrayed his cause, living in poverty and misery like the proletariat he defended, and left us a tremendous legacy.

I want to illustrate Yardımlı’s predicament by providing a contemporary example. Science illuminated İsmail Beşikçi, and he fought without compromising on the path shown by science, enduring many hardships as a result. So, what are the ‘subjective impulses’ that drive him? Could he not, like many others, have flattered his state and the academic morass of universities to become both wealthy and successful in his career? Which of these behaviours is captive to subjective impulses, and which one liberates the subject, the Us? Of course, the first liberates the Mind, while the second subjugates it to impulses and commodities. The Mind becomes the means of sustaining animal life, the commodity.

The first path, the path of science, reflects the subjective impulses of those walking in that direction, representing the general interest of humanity. They throw themselves into the vastness of science fearlessly, freely, and without doubt. Therefore, at the beginning of his monumental work, Marx states, “Just as there should be a portal to Heaven, at the entrance to science, all doubts should be cast out, and all fears should vanish.”

As a second example, I want to address Engels. He is Marx’s partner in theory. One should ask Yardımlı, what is Engels’ subjective impulse? If Marx’s concerns are about livelihood or personal issues, and a political commitment, is Engels’ impulse related to wealth and family issues as a political commitment? Thus, it seems that different subjective impulses can yield the same theoretical outcomes; whether you are poor or rich, when you lift your head and look at the reality of life flowing before your eyes, if you are not a blind or narrow-minded bourgeois intellectual, you will see life as Marx and Engels do, or rather, life will reveal its true face to you.

That is enough! Reducing people’s thoughts to their subjective impulses and explaining them through that lens is a folly that Yardımlı has not encountered for the first time, and we fear it will not be the last. Yardımlı moves from Marx to Marxism, saying, “Some, driven by a moral fanaticism for the task of saving a society, humanity, or philosophy they have imposed upon themselves, deny everything established and all acquired values.” Who? Marxism. Indeed! Those even remotely aware of the ‘m’ in Marxism would be left speechless by these sentences. Yardımlı’s views on Marxism are pure fabrications. Fabrication, that is, Construction, Speculation, and ultimately, Fictional Philosophy. After all, isn’t this the philosophical current A. Yardımlı calls us to? These sentences reflect Yardımlı’s deep insight into Marxism and the complex that lies deep within his subconscious.

Now, let us look at what Marxism is charged with in terms of its self-saving task: Society, humanity, and philosophy.

SOCIETY AND HUMANITY

Marxism has neither a task of saving society and humanity nor a proposition that understands it this way. Duty is an ethical responsibility. Marxism addresses facts not ethically but in their objectivity. Marxism is a worldview that uncovers the general laws of motion for all kinds of development. In a narrower sense, it is a system of thought that considers the laws of development of nature, society, and human thought within their historical context. Yardımlı’s expression carries the general misunderstanding related to Marxism. Thus, Marxism, as a scientific theory in this form, cannot take it upon itself to save humanity and society. Therefore, to correct it, it guides the struggles for the liberation of humans and societies. The human-historical development has its own objectivity. Perhaps Yardımlı has overlooked it, but it was Hegel who first discovered the historicity of human life and thought.

Marx ties the development of human history to class struggle, showing how this struggle manifests itself today, that is, in capitalism. He demonstrates that if the mutual struggle of classes on this historical ground results in the victory of the proletariat, humanity will transition to communism, that is, true human society, thus putting an end to the barbarism of humanity’s pre-history or history before humanity. These are not thoughts that descended from the heavens to Marx; they are laws of historical development, outside of the personal intentions of the subject, like Newton’s laws of physics or Darwin’s laws of evolution. For instance, just as the law of gravity cannot help people fly, the possibility of human flight is made possible by providing people with the necessary knowledge about nature. Marxism shows the tendencies of humanity’s historical development. Moreover, the method of approaching objectivity, and reality, excluding the subjective contributions of the thinker, as mere determinations of concepts, is undoubtedly shown in an idealistic manner by Hegel. Yardımlı appears to be entirely unaware of all this.

Yardımlı confuses Marxism with Hegelianism. In Marxism, there is no objective Mind that directs history as it pleases, dragging it from adventure to adventure. In Marxism, it starts not from the Mind, but from man as a real being. However, humans do not conduct their lives scattered and unrelated, like animals. They enter into necessary production relations to sustain their lives. Within these production relations, humans are divided into communities and classes. Therefore, it is clear that individuals sustain their lives first within the classes structured in social and production relations.

So, if it is not Us that propels this historical process and will save humanity today, then who is it? The working class is the one that will save all of humanity, along with itself, from the inhumanity it lives in. Marxism is the scientific theory of the proletariat that undertakes this saving task. “It is the historical task of the modern proletariat to carry out the work of saving this world. To deeply examine the historical conditions of this task and thus to provide consciousness to the class that is tasked with seeing this work, the oppressed class, about the conditions and nature of its own work: this is the task of scientific socialism, the theoretical expression of the proletarian movement.” Engels, Anti-A. Yardımlı

Thus, Marxism has no duty to save anyone, but it has a function as a scientific tool for the proletariat that undertakes the saving task. Sciences have emerged in humanity’s attempts to change nature and human nature and have helped people change nature and society in accordance with their interests and dominate them.

In summary, Yardımlı does not understand the historical position of science and Marxism as a worldview due to his misunderstanding of Hegel.

PHILOSOPHY

As Yardımlı states, Marxism does not attempt to save Philosophy either. The efforts of people to understand external reality, combined with the practical impossibility of grasping this reality, have confronted them with the reality of their own history, forcing them to embark on a speculative adventure instead of a scientific journey into the depths of nature.

Philosophy began with natural philosophers who attempted to interpret and explain nature solely through empirical data. Later, when people could not delve into the material roots of nature, they resorted to intellectual constructs, and ultimately, the development of productive forces and sciences revealed the material causalities of nature, thereby burying speculative philosophy in history. Philosophy has transcended in this form, moving from philosophy as such to the natural sciences, and the content of philosophy has transitioned to the sciences. Philosophy, in this form, has been overcome.

“After all, this is no longer a philosophy but a simple worldview that will demonstrate and utilize its utility within real sciences, apart from separate sciences. Thus, the philosophy here has been removed, that is, it has been overcome in the sense that it is both ‘surpassed and preserved’, and has been preserved in its real content.” Engels, Anti-Dühring

Marxism, therefore, objectively explains the historical development and roots of thought, religion, art, and philosophy. Marxism is a revolutionary theory; it never engages in the task of saving the dead or the dying. However, it explains that it does so within the objective internal relations and historical continuum.

Those who panic in the face of these objective historical developments and attempt to stop the world from dying, even trying to turn it back a few centuries (Yardımlı is proposing a return to antiquity) are pure philosophical reactionaries. These are the burdens of the various ‘newly’ labelled bourgeois philosophical currents proposed by Yardımlı.

ESTABLISHED EVERYTHING, ACQUIRED VALUES

Contrary to A. Yardımlı’s claims, that Marxism does not deny everything established and all acquired values. It demonstrates that social development progresses through the conflicts of existing contradictions within it and explains that the future society will be shaped by the progressive segments of the conflicting sides of the past society: “No social formation disappears before it has developed all the productive forces it is capable of containing; new and higher production relations cannot come to take the place of old ones without blossoming within the womb of the old society.”

In other words, it explains that all acquisitions beneficial and necessary for humanity will be taken by future society and that the class tasked with saving humanity’s future, the proletariat, can only realize its and society’s liberation by dismantling all obstacles to the liberation (humanization) of humanity. This framework shows the way to clear the path for the endless development of humanity’s productive forces by dismantling all the regressive and anti-progressive forces within it. Marxist principles thus emerge as the principles that will clarify the path and lead humanity toward its future.

Footnotes

- Hegel, G. W. F. Science of Logic. Translated by George di Giovanni. Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 1.

- Yardımlı, A. Constructive Philosophy and its Challenges. [Publisher], [Year], p. [insert page number]. (Please fill in the publisher and year information as needed.)

- Marx, K., & Engels, F. The German Ideology. Edited by C. J. Arthur. Lawrence & Wishart, 1970, p. 135.

- Yardımlı, A. Constructive Philosophy and its Challenges. [Publisher], [Year], p. [insert page number]. (Please fill in the publisher and year information as needed.)

- Husserl, E. Logical Investigations. Translated by J. N. Findlay. Routledge, 2001, p. 45.

- Kant, I. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood. Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 70.

- Comte, A. The Positive Philosophy. Translated by Harriet Martineau. Chapman, 1853, p. 210.

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. Harper & Row, 1962, p. 44.

- Marx, K. Capital: Critique of Political Economy. Volume 1, Penguin Classics, 1990, p. 92.

- Beşikçi, İ. The Kurdish Question: A Scientific Analysis. [Publisher], [Year], p.

- Engels, F. Anti-Dühring: Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science. Progress Publishers, 1975, p. 118.

- Yardımlı, A. Constructive Philosophy and its Challenges. [Publisher], [Year], p.

- Marx, K. The Capital, Volume 3. Penguin Classics, 1991, p. 95.

- Yardımlı, A. Constructive Philosophy and its Challenges.

Review

98%

Summary A PHILOSOPHER'S FICTIONALISED SEARCH FOR PARADISE Contrary to A. Yardımlı's claims, that Marxism does not deny everything established and all acquired values. It demonstrates that social development progresses through the conflicts of existing contradictions within it and explains that the future society will be shaped by the progressive segments of the conflicting sides of the past society: "No social formation disappears before it has developed all the productive forces it is capable of containing; new and higher production relations cannot come to take the place of old ones without blossoming within the womb of the old society."

RECENT COMMENTS